How many nuclear weapons are there in the world? Experts warn of a possible arms race.

The unprecedented attack launched by Israel against Iran, with the stated aim of preventing the country from developing atomic weapons , has once again focused international attention on the latent nuclear threat . Since last Friday, June 13, Israeli aircraft have attacked various strategic infrastructure, including air defense systems, ballistic missile depots, and nuclear plants in Natanz, Isfahan, and Fordow , under the justification of suspicions that Iran may be enriching uranium for weapons purposes.

Despite the Israeli offensive, international assessments, including U.S. intelligence findings, affirm that Iran's nuclear program is not currently militarized . However, and although Tehran has also insisted that it is not building a bomb and that its program is solely for peaceful energy purposes—which include building more nuclear plants for domestic demand—according to the United Nations International Atomic Energy Agency, no other country has the type of uranium that Iran possesses without having a nuclear weapons program .

But whether or not Iran currently has atomic bombs, the world's nuclear inventory is estimated to have some 12,241 warheads . According to the most recent report by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) , 9,614 of these were part of the military arsenal available for potential use.

“An estimated 3,912 of these warheads were deployed on missiles or aircraft, with the remainder stored in central depots. Around 2,100 of the deployed warheads were on high operational ballistic missile alert. Nearly all of these warheads belonged to Russia or the United States , although China may now maintain some missile-mounted warheads even in peacetime,” the SIPRI report states.

The institute emphasizes that since the end of the Cold War , the gradual dismantling of retired warheads by Russia and the United States has typically outpaced the deployment of new warheads, resulting in a year-over-year decline in the overall nuclear inventory. However, they are concerned that this trend could reverse in the coming years because the pace of dismantlement is slowing while the deployment of new nuclear weapons is accelerating.

SIPRI experts are concerned that “a new and dangerous nuclear arms race is emerging around the world at a time when arms control regimes are severely weakened .” “Global nuclear arsenals are expanding and modernizing. Nearly all nine nuclear-weapon states—the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, China, India, Pakistan, the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea), and Israel—continued intensive nuclear modernization programs in 2024, upgrading existing weapons and incorporating newer versions,” says the SIPRI 2025 report.

“The era of reducing the number of nuclear weapons worldwide, which has lasted since the end of the Cold War, is coming to an end,” said Hans M. Kristensen, Senior Research Fellow at SIPRI’s Weapons of Mass Destruction Program and Director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS). “Instead, we are seeing a clear trend of increasing nuclear arsenals, more aggressive nuclear rhetoric, and the abandonment of arms control agreements.”

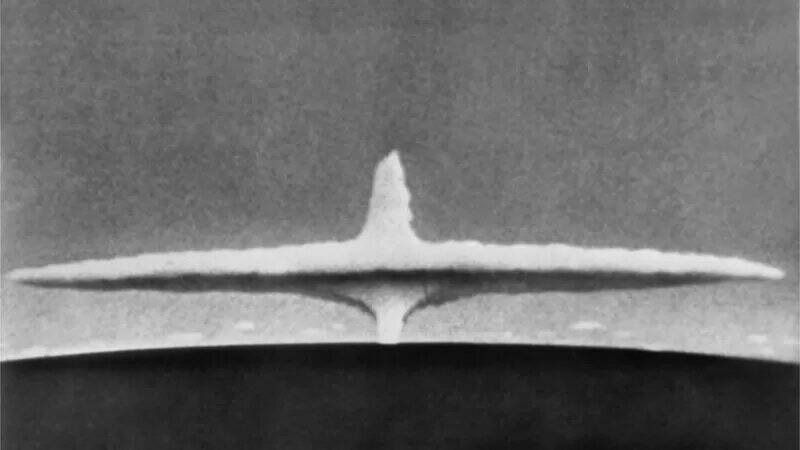

There are some photographs showing the scale of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki explosions. Photo: AFP

According to SIPRI, Russia and the United States together possess around 90 percent of all nuclear weapons. The size of their respective military arsenals (usable warheads) appears to have remained relatively stable in 2024, but both countries are pursuing extensive modernization programs that could increase the size and diversity of their arsenals in the future.

"If a new agreement is not reached to limit these arsenals, the number of warheads deployed on strategic missiles is likely to increase following the expiration of the 2010 bilateral Treaty on Measures for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms (New START) in February 2026 ," SIPRI warns.

Other countries that stand out for their nuclear inventory include China, which is estimated to currently possess at least 600 nuclear warheads. Its nuclear arsenal is growing faster than any other country's, with approximately 100 new warheads added annually starting in 2023. "By January 2025, China had completed—or was close to completing—approximately 350 new intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) silos in three large desert fields in the north of the country and in three mountainous areas in the east," Sipri reports.

The destructive power As is often the case with technology, it advances, is updated, and improves. This has not been the case in the field of warfare and nuclear weapons, with their destructive power increasing. As a reference, we have the first generation, characterized by the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 , the only ones ever used during a war. The first, called Little Boy, weighed 15 kilotons (Kt), and the second, Fat Man, weighed 20 Kt. A single kiloton is equivalent to 1,000 tons of TNT.

After these bombs, the result of the Manhattan Project—which involved scientists such as Robert Oppenheimer, Niels Böhr, and Enrico Fermi—others of greater power have emerged. There are, for example, the W-80 and W-87 , which are part of the US arsenal, with a yield of 150 and 300 kt respectively, up to the Tsar Bomba , the most powerful bomb tested by the former Soviet Union, a 50-megaton (or 50,000 kt) hydrogen bomb that was detonated in the air in 1961.

Advances have occurred not only in the destructive capacity of nuclear weapons, but also in improved methods for delivering them to their targets, with intercontinental ballistic missiles that can carry their payload, whether a nuclear warhead or another type of weapon, thousands of miles. This is the case with the Minuteman III missiles deployed by the U.S. in Colorado, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, and Wyoming.

But, in principle, the destructive power of nuclear weapons is still due to the same principles of physics that were taken into account when they were created. According to Diego Torres, a professor in the Department of Physics at the National University of Colombia and a visiting researcher at the Laboratory for Nuclear Sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), in a classic atomic bomb, like those used in Japan, a very large, very rapid and uncontrolled release of energy occurs when the nuclei of atoms split .

"In nuclear fission, heavy nuclei like uranium and plutonium are taken, and when they split, they generate an enormous amount of energy, heat, and radiation. That energy is released, and a bomb of this type would more or less vaporize everything from downtown Bogotá to the National University," Torres says.

The fission process, which is the same process used to generate energy in nuclear reactors, involves bombarding the atomic nucleus with high-speed neutrons. "Protons and neutrons have a lot of energy that keeps them together, and breaking them apart isn't easy, but when a neutron hits them with that speed, all of the atom's energy is released," explains Jairo Alexis Rodríguez, a doctor in Physics and also a professor at the National University. The explosion's massive magnitude is achieved thanks to a chain reaction where neutrons from the already broken nuclei generate fission in other atoms.

The other type of nuclear bomb uses the opposite process: nuclear fusion . Torres explains that this is the same energy with which the sun produces light and heat. "Hydrogen isotopes are combined, and in the process of fusing them, approximately 7,000 times more energy is released than would be released in a nuclear fission bomb," the professor explains about these bombs, also known as thermonuclear bombs. To capture the magnitude of this type of weapon, to which the Tsar Bomba belongs—one of the most lethal—he adds that this particular one would be capable of vaporizing the entire Bogotá savannah.

These hydrogen bombs require a lot of energy to achieve fusion, which is why they are usually triggered by a fission bomb. This also makes them much more dangerous and unstable. "We haven't been able to control nuclear fusion; there are several laboratories around the world trying to do so because it produces so much energy that it could, paradoxically, be a hope for meeting the needs of Europe, for example," says Professor Rodríguez about the initiatives being advanced in this area in France, with the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) project.

With just one reactor of this type, the European Union would no longer depend on Russian gas to meet its energy needs. "That energy is incredibly clean if we can harness it; we have to be vigilant about that as a country and as a society," says Torres.

According to the professor, nuclear technology has led to significant advances in various fields, such as cancer treatments, diagnostic imaging, mine detection, and energy production, among others. He therefore believes it should not be demonized for its military use.

For now, in this area, we hope that the idea of a possible nuclear war remains remote, one that would test what scientists have for years speculated could happen in the event of continuous nuclear explosions, causing the deaths of millions of people and triggering the nuclear winter proposed by Carl Sagan and other scientists since the 1980s.

eltiempo