EPSs no longer manage the money; now the government allocates most of the resources: has that improved the health system?

One of the diagnoses insisted upon by President Gustavo Petro's government has been that the health crisis is largely due to the fact that the EPSs, as private entities, manage the resources. That is why one of the cornerstones of the reform project is that insurers would no longer be responsible for managing the country's health funds, which average around $100 billion pesos annually. Instead, Adres, a state entity, would directly transfer funds and pay hospitals, clinics, and pharmaceutical companies for the services provided to users.

However, given the complex progress of the reform bill in Congress, in April of last year the government issued a decree allowing for changes to the conditions for increasing the funds allocated directly. Thus, the EPSs that did not meet the requirements (which were the majority) would no longer manage health resources, but instead, Adres would directly pay clinics and hospitals, subject to certain parameters.

"The law allows us to make direct payments to public and private hospitals and clinics, and we will do so to make more efficient use of public health resources," said President Gustavo Petro on April 8 of last year, days before the issuance of Decree 0489 of 2024 , by which Adres would begin to allocate the funds corresponding to the UPC and the Maximum Budgets.

President Gustavo Petro has insisted on a direct transfer as a solution. Photo: Presidency / Screenshot from Change.org

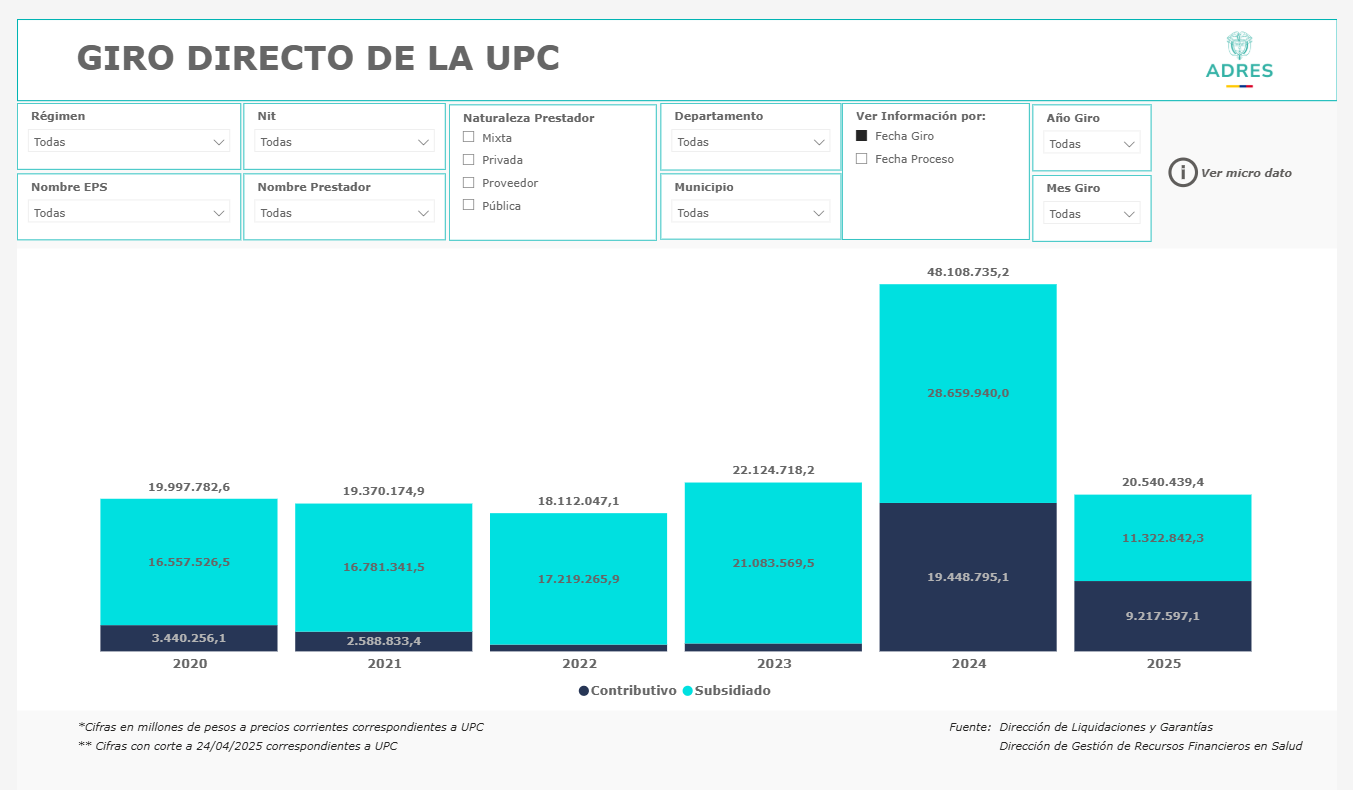

Barely a year later, the Ministry of Health's decree has yielded results. According to data from Adres, in 2024, $57 of every $100 pesos transferred by that entity to pay for services covered by the UPC did not go through the EPS; instead, they were transferred directly to clinics and hospitals. In total, $48.1 billion pesos of health resources were paid through direct transfers last year. So far this year, as of April, $20.5 billion pesos have been transferred through this mechanism.

Direct transfer in billions made by Adres in the last five years. Photo: Adres

While the EPSs continue to nominate clinics and hospitals to make this payment, the Government, through the Health Superintendency, currently controls more than 60% of the members, with the nine EPSs under intervention and one EPS under special surveillance. This means that the Government not only makes the direct transfer, but also, through the Superintendency of Health, nominates and approves the Health Provider Institutions (IPS) to be paid, which last year totaled 7,291.

In this sense, the government has now achieved, without the need for reform, one of the changes it had most requested to transform the system: that the EPSs not handle the funds, but rather that the State would be responsible for paying for what patients receive. Today, a new draft decree seeks to increase the scope of this direct transfer. Currently, the direct transfer has a cap, meaning only 80% of what the EPS would receive can be transferred directly; the other 20% still goes to the insurer for management. Now, a new draft decree published for comment by the Ministry of Health seeks to increase this cap to 90%.

Health Minister Guillermo Alfonso Jaramillo. Photo: Ministry of Health

Having achieved these increases in direct transfers, as the government, President Petro, and his Minister of Health, Guillermo Alfonso Jaramillo, have requested for months, has this been enough to improve health services? According to the data, everything indicates no.

So far, what the figures show is that, instead of improving, the situation has worsened in the EPSs where direct transfers are currently being made. These are mostly those under the control of the Superintendency of Health (SUPH) and account for more than 60% of the system's members. This is because even if the government makes the direct transfer, users remain affiliated with an EPS, which is theoretically responsible for their service, although they no longer receive much of the payment they previously received for providing said service.

For example, in the case of Sanitas, the indicators have been declining over the past year, reflecting the discontent of its members. In 2023, Sanitas received a total of 185,634 complaints, and in 2024, it received 221,565, representing a 19 percent increase in complaints and claims from this EPS's users.

In the months prior to the intervention, that is, January, February, and March 2024, Sanitas accumulated 15,071, 15,721, and 14,367 complaints, respectively. A year later, during the Supersalud intervention, the insurer recorded 23,495 complaints in January and 20,931 in February 2025. A source close to the intervention told EL TIEMPO that the PQRDs (Reportedly Delinquent Claims) have been the main headache during the process. “There were complaints averaging 22,000 and 23,000 per month. However, in November (2024), the number dropped to 21,000,” the source explained.

For Sanitas users, neither the intervention nor the direct referral has resulted in better care. Photo: SANITAS

The same thing has happened with Nueva EPS. According to Supersalud figures, in February 2024, the PQRD rate at Nueva EPS was 21.26 per 10,000 members, and by February of this year, it had risen to 34.88, the highest figure in the last three years.

But the situation at Sanitas and Nueva EPS is not an isolated one. According to data from the Supersalud (Health Superintendency of Health), the rate of complaints per 10,000 members has increased in eight of the nine EPSs under intervention, with the largest increases in Servicios Occidental de Salud (SOS), Famisanar, Nueva EPS, Sanitas, and Savia Salud.

On the other hand, and despite the fact that direct payments have accelerated payments, this year a growing number of Health Care Providers (IPS) and pharmaceutical managers have decided to stop serving Nueva EPS members due to the multimillion-dollar debts the insurer has not paid, which prevents them from continuing to offer services such as hospitalizations and medication delivery.

According to Pacientes Colombia spokesperson Denis Silva, while the organization has always supported direct funding, it has not seen any improvement in Colombians' right to health care. In fact, in his opinion, there has been a regression in patient care, and there are doubts about where the money is being spent.

“When you talk to public and private providers and pharmaceutical managers, they all say they're not getting the money. So we ask ourselves: Is Adres transferring funds to shell companies, or where is the money going? The second thing is that the EPS decides where the money goes; that is, this IPS gets paid, and this one doesn't. A specific case is the Subred (National Health Network) in Valle del Cauca, where the comptrollers appointed by the Superintendency of Health seem to be running a business where the EPS authorizes and the comptroller refuses to authorize payment. So something is going on,” Silva asserts.

Patients Colombia spokesperson Denis Silva. Photo: Private Archive

Despite the increase in direct transfers, which the government claims would improve resource management, in eight of the ten EPSs controlled by Supersalud, debts with clinics and hospitals grew in just six months, according to a report by the Colombian Association of Hospitals and Clinics (ACHC).

According to the data, as of December 2024, the debt owed to its members amounted to 20.3 trillion pesos, representing an increase of 6.9% (approximately 1.3 trillion pesos) compared to the previous study, as of June of the same year. The report also shows an increase in the value of the non-performing loan portfolio and its concentration. While in June 2024, non-performing loans represented 55%, by December 2024 it had reached 55.3%, an increase of more than 770 billion pesos between the two periods.

According to Cristina Isaza, executive director of the Plural Citizen Participation Group, while it's true that the increase in direct transfers has centralized the management of funds, this hasn't resolved the system's structural problems, as the government predicted. This, she says, has led to patients remaining in the same situation or worse off, in a situation where it's difficult to access medical appointments, medications, or answers.

“The operational capacity of the EPSs was weakened without a clear or functional alternative model, resulting in more resources in the hands of the State, but less control and more uncertainty for those who must provide and receive the service. There is no evidence of real improvements: neither in timeliness, quality, nor coverage. Taking money away from private companies and giving it directly to clinics and hospitals sounds good on paper, but in practice it has generated disorder, a lack of auditing, and administrative chaos. There are no clear rules or prioritization criteria, and procedures still depend on EPSs that are in intensive care ,” Isaza emphasized.

For his part, Luis Jorge Hernández, a public health specialist and researcher at the University of the Andes, emphasizes that while the direct transfer is an administrative advance, as it has improved the liquidity of some IPSs that were experiencing financial difficulties, this does not replace a structural reform that could strengthen the quality, timeliness, and equity of the Colombian health system.

“This measure has improved the liquidity of many providers and reduced financial intermediation, one of the system's long-standing problems. However, this change has not necessarily translated into better care for patients. Although hospitals receive money more quickly, delays, fragmented care, and a lack of comprehensive coverage persist in several regions of the country,” Hernández emphasizes.

Former Health Minister Augusto Galán is more emphatic, stating that so far there is no evidence that the direct transfer has helped improve patient care. He even questions whether it is actually helping the IPSs, as many continue to report that they are owed resources and that there are increasingly fewer funds available from the State to pay for healthcare, as the increase in the UPC for this year was lower than expected. “There is no evidence to show any improvement. On the contrary, the deterioration in access continues, and the direct transfer is not necessarily improving the financial situation of clinics, hospitals, logistics operators, and other entities that operate the health system,” Galán added.

Environment and Health Journalist

eltiempo