Rosalía Is the Ultimate Romantic

One Wednesday morning in June, Rosalía decided to start her day with a pensive walk in the woods. She ambled up the steep trail at the Carretera de les Aigües—Barcelona’s answer to Runyon Canyon in the Hollywood Hills—and peered out into the distance toward Sant Esteve Sesrovires, the Catalan town where she grew up. She slipped on a pair of headphones and listened to The Smiths’ compilation album, Louder Than Bombs.

As she recalls the scene to me now, she mimics Morrissey’s yearning croons, in the supple vibrato of her own voice. Lifting her manicured hand, exulting in the melodrama of it all, she sings, “Please, please, please let me get what I want…this time.”

This is how we start our conversation inside Pècora, a chic, minimalist coffee shop in the seaside neighborhood of Poblenou that has opened just for us. Rosalía is sitting with her back to the windows—so that potential customers would squint at the Closed sign and overlook the country’s most game-changing pop star on the other side of the glass. She’s wearing a floor-length Gimaguas dress in baby blue plaid, revealing Dior biker boots when she crosses her legs. Her long curls cascade around her shoulders when she leans in to talk.

“The rhythm of everything is so fast, so frenetic,” says Rosalía, who turns 33 in September. “And I think, ‘My God, it’s been eight years since I released my first work.’ That’s insane to me.”

When we meet, it seems as though Rosalía is pushing her way through a creative impasse. Her forthcoming album, the follow-up to 2022’s Grammy-winning Motomami, is yet to be completed. “What is time?” she says, laughing. “That’s so relative! So there’s always a deadline and, well, the deadline can always change.”

Although she won’t divulge what her new record sounds like just yet—she’s quite elusive about the whole thing, really—she’s shared videos of herself writing and producing tracks as part of a creative campaign for Instagram, as if to prove to fans that she is, indeed, at work. In fact, she’s scheduled time at a local studio immediately after our chat to fine-tune her new material. “I’m in the process,” she says.

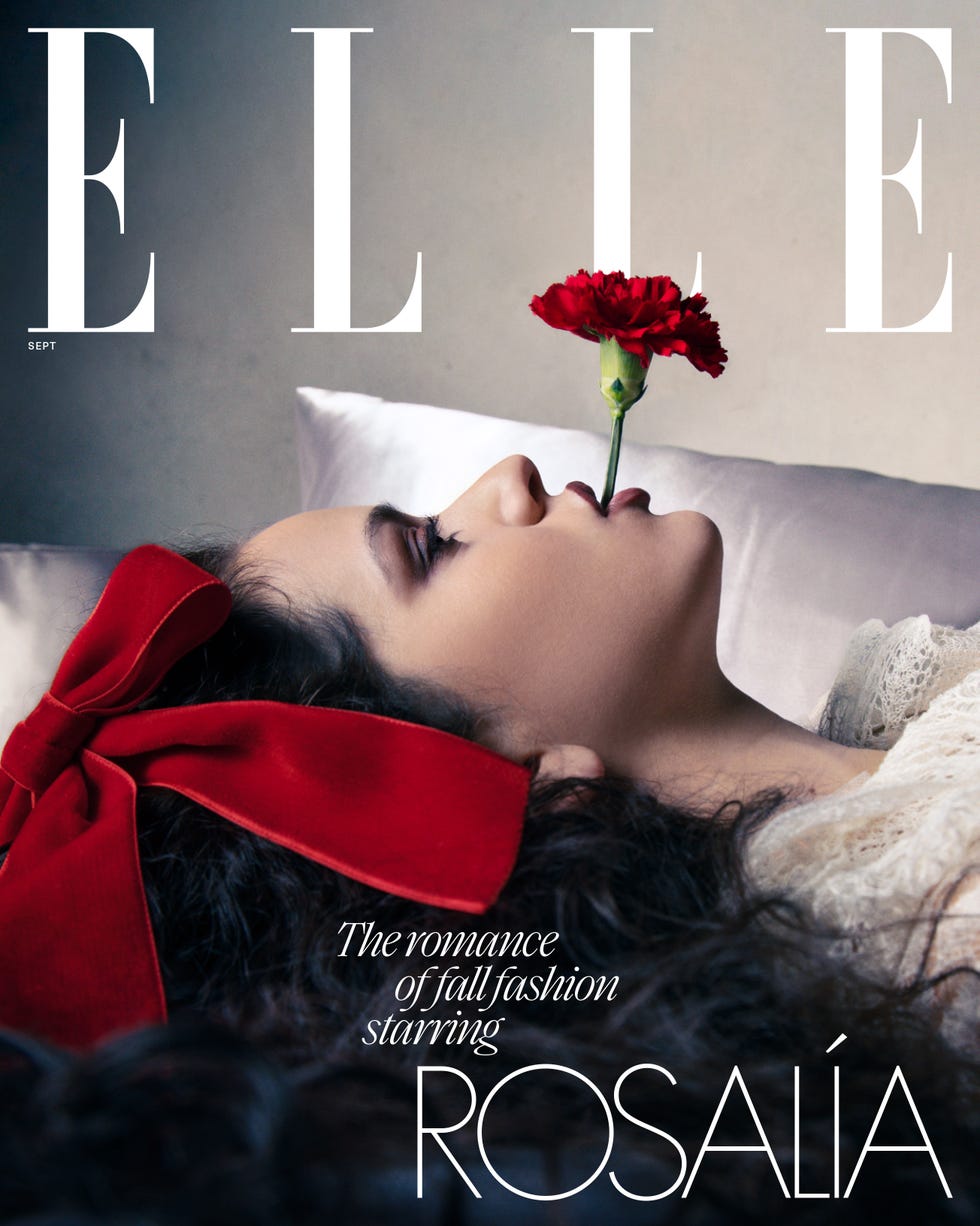

Bow, Jennifer Behr.

Of course, there’s no shortage of distractions to be had this summer. She wedged our conversation between visits with her family and a detour to Barcelona’s famed Primavera Sound festival with her sister, Pili. Soon she’ll return to Los Angeles to film the remaining scenes for her guest-starring role in HBO’s Euphoria. She’s also been seen in Los Angeles, Munich, and Barcelona with her rumored love interest, the German actor-singer Emilio Sakraya. Regarding her dating life, she only says, with a wide, playful grin: “I spend many hours in the studio. I’m in seclusion.” Her closest relationship right now may be with her piano.

“The driving force that leads you to continue making music has to come from a place of purity. Motives like money, pleasure, power…I don’t feel that they are fertile. Nothing will come out of there that I’m really interested in.”

The global anticipation for new music is understandable. In her major label debut under Universal Music Spain, 2017’s Los Ángeles, she introduced newcomers to the brooding Spanish flamenco standards that she studied at the prestigious Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya. Rosalía then entered the Latin pop stratosphere with her 2018 sophomore album, El Mal Querer—which also served as her baccalaureate thesis, using the 13th-century novela Flamenca as source material to illustrate the workings of an abusive relationship. El Mal Querer would go on to win the Latin Grammy for Album of the Year, then the Grammy for Best Latin Rock or Alternative Album.

In 2022, she dropped Motomami, a bold work of avant-pop daredeviltry, inspired by music from the Caribbean and fortified with the dauntless, feminist spirit of her mother, who took young Rosalía out for rides on the back of her Harley-Davidson. Motomami won her the same two prestigious Grammy categories as the previous album—a feat that catapulted Rosalía to global stardom, yet inevitably raised the bar for future projects. The pressure to answer to industry demands, she says, is increasingly at odds with her freedom-seeking spirit.

Dress, Dior.

“The rhythm [of the music industry] is so fast,” Rosalía tells me. “And the sacrifice, the price to pay, is so high.” The only way she can continue without burning out is if her motives feel true. “The driving force that leads you to continue making music, to continue creating, has to come from a place of purity,” she says. “Motives like money, pleasure, power…I don’t feel that they are fertile. Nothing will come out of there that I’m really interested in. Those are subjects that don’t inspire me.”

To begin her next chapter, Rosalía sought space far from Spain, in the quiet of Mount Washington, a hilly enclave in northeast Los Angeles. There, she worked from a private music studio, recording songs she’d written almost entirely from bed in a nearby Hollywood apartment. She broke up her days with films by Martin Scorsese and Joachim Trier, and read the novel I Love Dick, a feminist inquiry of desire by Chris Kraus. (“I love this woman! I love how she thinks,” she says of Kraus.)

In L.A. last summer, paparazzi caught Rosalía outside Charli XCX’s 32nd birthday party wielding a bouquet of black calla lilies filled with cigarettes, sparking a microtrend. (“If my friend likes Parliaments, I’ll bring her a bouquet with Parliaments,” Rosalía says. “You can do a bouquet of anything that you know that person loves!”) She also made frequent stops at the local farmers market, where she says she tapped into her primordial gatherer spirit.

Dress, Zimmerman. Bow, Jennifer Behr. Earrings, Juju Vera.

“Many times, the more masculine way of making music is about the hero: the me, what I’ve accomplished, what I have…blah blah blah,” she says. “A more feminine way of writing, in my opinion, is like foraging. I’m aware of the stories that have come before me, the stories that are happening around me. I pick it up, I’m able to share it; I don’t put myself at the center, right?”

It is a method she cultivated as an academic, which directly informs her approach to composition. Like works of found-object art, her songs are assemblages of sounds with seemingly disparate DNA, brought together by her gymnastically limber voice. In her 2018 single “Baghdad,” she interpolated an R&B melody made famous by Justin Timberlake; in her 2022 smash “Saoko,” she rapped over jazz drum fills and pianos with sludgy reggaeton beats.

The visual culture of Rosalía’s work is executed with similarly heady intentions, inspired by TikTok videos and the fractured nature of her own presence on the internet. A staple of her Motomami world tour was the cameraman and drones that trailed her and her dancers across the stage. One of my most lasting memories from her shows was just the internal frenzy of deciding whether my eyes would follow Rosalía, the real live person on stage, or Rosalía, the image replicated and multiplied on the screens behind and around above her.

“In a cubist painting, which part do you choose?” says Rosalía of her concept. “Everything is happening at the same time, right? So you just choose what makes sense for you, where you want to put the eye and where you want to focus your energy.”

She’s gone mostly offline since her last project. “Björk says that in order to create, you need periods of privacy—for a seed [to] grow, it needs darkness,” she says. She has also shed some previous collaborators, including Canary Islander El Guincho, the edgy artist-producer who was her main creative copilot in El Mal Querer and Motomami. She says there is no bad blood, though “we haven’t seen each other [in] years. I honestly love working with people long-term. But sometimes people grow apart. He’s on a journey now, he’s done his [own] projects all these years. And yes, sometimes that can happen where people, you know, they grow to do whatever their journey is. Right now, I’m working by myself.”

Going it alone poses a new challenge for Rosalía, who, in true Libran fashion, derives inspiration from the synergy she experiences with others. She has famously collaborated with past romantic partners, like Spanish rapper C. Tangana, who was a co-songwriter on El Mal Querer. In 2023, she released RR, a joint EP with Puerto Rican singer Rauw Alejandro, to whom she was engaged until later that year. She does not speak ill of her exes, if at all, but simply says, “I feel grateful to each person with whom life has made me find myself.”

Rosalía was also linked to Euphoria star Hunter Schafer, who, in a 2024 GQ story, confirmed their five-month relationship back in 2019, and described the singer as “family, no matter what.” When I ask Rosalía if the experience put pressure on her to publicly define her sexuality, queer or otherwise, she shakes her head. “No, I do not pressure myself,” she says. “I think of freedom. That’s what guides me.”

Dress, Ferragamo. Corset, Agent Provocateur. Bow, Jennifer Behr.

The two remain friends and, more recently, costars: Earlier this year, Rosalía began shooting scenes for the long-awaited third season of Euphoria. She appreciates the controversial, controlled chaos engendered by the show’s writer, director, and producer, Sam Levinson. Equally a fan of the singer, Levinson tells ELLE that he gave her almost free rein to shape her part. “I love unleashing her on a scene,” he says. “I let her play with the words, the emotions, in English and Spanish. I never want to tell her what to do first, because her natural instincts are so fascinating, charismatic, and funny. Every scene we shoot, I’m behind the camera smiling.”

Rosalía, who first developed her acting chops through the immensely theatrical art of flamenco, says that she likes to put herself “in service of the emotion, in service of an idea, in service of something that is much grander than me.” Although she can’t share much about her role while the season is in production, she says she’s enjoyed running into Schafer on set, and developing rapport with costars Zendaya and Alexa Demie. “I have good friends there. It feels really nice to be able to find each other.”

Rosalía’s first foray into professional acting was in Pain and Glory, the 2019 film by the great Spanish director Pedro Almodóvar. Before filming, Almodóvar invited the singer out to lunch with her fellow countrywoman and costar Penélope Cruz. They would play laundresses singing together as they washed clothes in the river. “I was terrified to have to sing with her,” Cruz recalls. “She was nervous about acting, and I was nervous about singing—and it was funny to be sharing that nervousness.”

Cruz and Rosalia would become great friends—two Spanish icons who have brought their country’s culture to a global audience. But between the two divas, there existed no air of gravitas—only genuine, hours-long talks and banter built on mutual admiration. “I’ve always been mesmerized by her voice,” Cruz says, “and her talent also as a composer, as a writer, as an interpreter. The way she performs and what she can transmit is something really special.” She notes that Rosalía’s artistry has had a ripple effect in Spain, sparking a wave of experimentation.

It’s a legacy that Rosalía helped accelerate, but she declines to take credit for it. She’s more inclined to cite her forefathers in flamenco, Camarón de la Isla and Enrique Morente, as well as Björk and Kate Bush, who she says are part of the same matriarchal lineage in pop. “[If] Kate Bush exists, and then Björk exists, then another way of making pop exists,” Rosalía says. “I couldn’t make the music I make if there wasn’t a tradition behind it, which I could learn from and drink from. I hope that in the same way, what I do can make sense for other artists.”

“I want every character I play to be complicated and deep and have layers to them, because that’s what it is to be human. Like with Kate in Twisters, I know there was a big uproar that there wasn’t a kiss at the end. But she went on a journey in that film that was bigger than a romantic journey.”

But when it comes to matters of fashion, Rosalía is much more protective of her own steeze, an ultrafemme, Venus-like biker chic she’s spent her life cultivating. “Girl,” she says, motioning at her own body, “I am a moodboard in flesh! I feel that as an artist, I cannot only express myself through music. You can be creative in your life 24-7. It’s just about allowing yourself to be in that state. For me, style is an elongation, an extension of the expression.”

Yet before we leave, she stresses that—whether she releases one more album in her life, or 20—music will be the compass that orients her for the rest of her days.

“It’s funny when people say I quit music,” Rosalía says. “That’s impossible! If you are a musician, you can’t quit. Music is not something you can abandon.

“Sometimes it takes a second for you to be able to process what you’ve done,” she adds. “It’s a blessing in an artistic career to process things, or rewrite how it should have been done before—in your life or in anything. The immediacy of today’s rhythms is not the rhythm of the soul. And to create in an honest way, you have to know what rhythm you’re going with.”

Hair by Evanie Frausto for Pravana; makeup by Raisa Flowers for Dior Beauty; manicure by Sonya Meesh for Essie; set design by Lauren Nikrooz at 11th House Agency; produced by John Nadhazi and Michael Gleeson at VLM Productions.

This story appears in the September 2025 issue of ELLE.

elle