The indomitable judge from Weimar: “They were very, very stressful years”

A judge rules against the coronavirus measures. Today we know: He was right. But that didn't help him. He lost his job and was left with nothing.

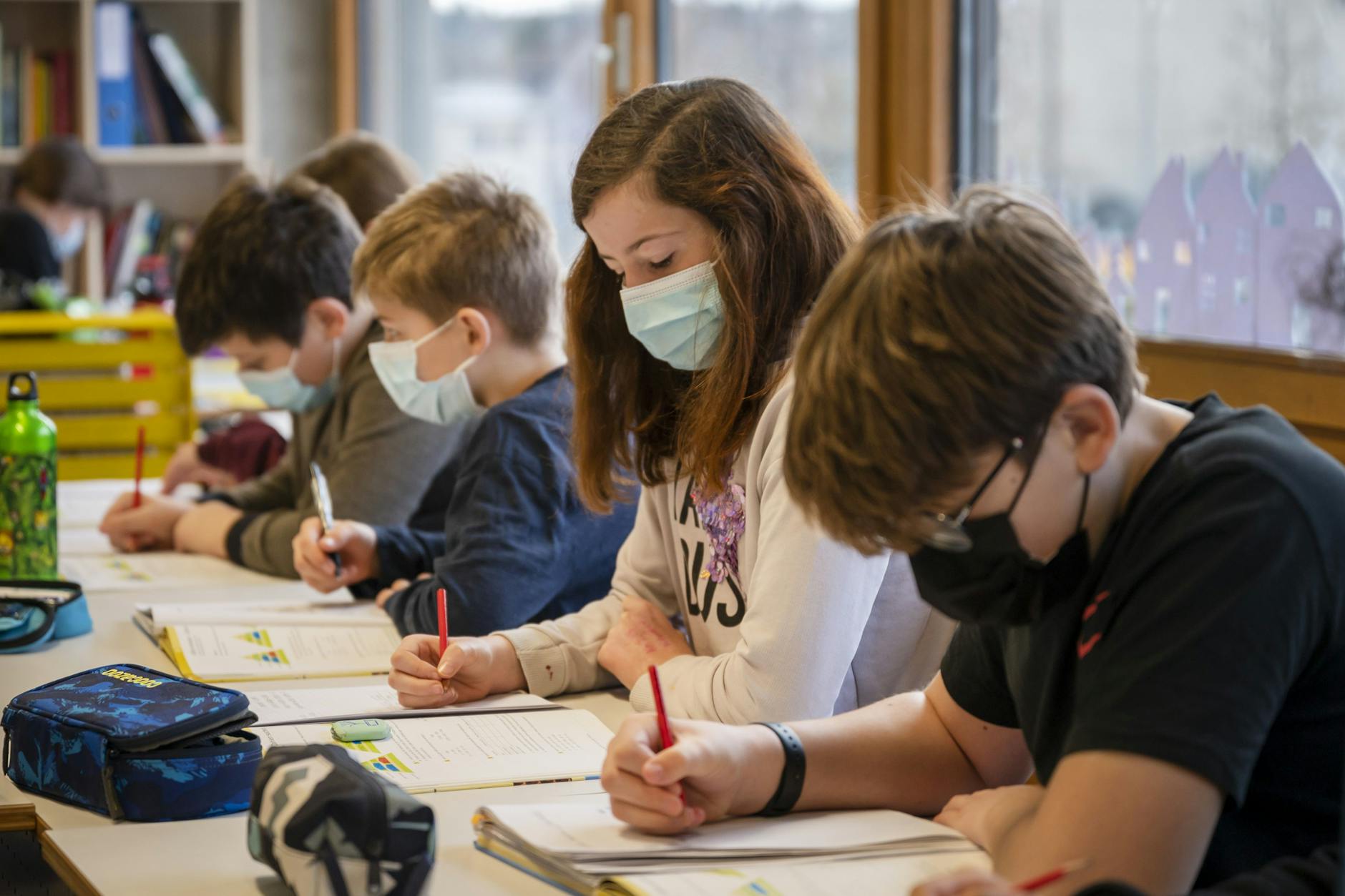

Weimar family court judge Christian Dettmar has lost his job and is left with nothing. He was convicted for committing a formal error in a ruling on mandatory mask wearing: He should have kept notes on his communications with those affected. Suddenly, he was branded a conspirator. No court addressed the matter itself. The expert opinions Dettmar requested were ignored—even though the RKI files and other scientific findings subsequently fully confirmed the dubious nature of the measures. A record of a case that could make one lose faith in justice.

Mr. Dettmar, how did you come to issue court orders against mandatory mask wearing and mandatory testing in schools?

At the end of 2020 and the beginning of 2021, parents repeatedly approached me, sometimes during breaks in negotiations or on other occasions. They asked me whether anything could be done about these measures in schools, which place an extreme burden on their children and, indirectly, on their parents. I had already looked into the issue. At the beginning of 2021, together with a colleague here in Weimar, I became a founding member of the "Critical Judges and Public Prosecutors" ( KRiStA ) network. To obtain legal action, an affected party can submit a "suggestion."

At some point, I had a suggestion on my desk from a mother who had two sons at two schools here in Weimar. One of primary school age and one in a regular school, i.e., a secondary school. She suggested that the measures be reviewed. It concerned the mandatory mask wearing and testing. I did what I've done many times in my professional career. I initiated interim injunction proceedings and, in parallel, main proceedings. In the main proceedings, I obtained three expert opinions: from hygiene professor Ines Kappstein, biologist Ulrike Kämmerer, and psychologist Christof Kuhbandner, who represent different disciplines.

The court accused you of saying the experts were old acquaintances. Is that true?

At first, I only contacted Professor Kappstein. I explained to her the questions I had or might have. I've always done that. Whenever I had experts I'd never had in my courtroom before, I always called them and asked two questions. First, whether they had the necessary scientific expertise for certain of my questions. And second, whether they could also prepare a possible expert opinion within a reasonable time. Experts often don't have time at all. I had also asked these questions of Professor Kappstein. She told me that she had expertise for certain, but not all, questions. For the remaining questions, she referred me to her two colleagues. I had heard of them before, but didn't know them. So, I obtained expert opinions from three professors with different questions in the main proceedings. They then came forward. They were the only expert opinions that had existed on the topic up to that point. On this basis, I then issued a preliminary injunction.

The verdict against you reads as if it was a conspiracy. Who is behind the KRiStA network?

So the word "conspiracy" is completely out of place. These are honored colleagues, prosecutors and judges, both active and retired. We have a website. Anyone can find it online. It also contains our statutes and our mission statement. We've been publishing articles on legal topics on this website for several years now. You can also write letters to the editor about it. Everything is completely transparent. Some people try to create the impression that the KRiStA is dubious. That's fundamentally wrong.

Would you say that this network is, so to speak, a specialist information platform that existed before you became involved in the mask issue?

Yes, it was founded in early 2021, and my decision was made on April 8, 2021.

Did you tell the experts what they wanted their report to say?

I stated my questions, and, as always, I hoped that my reviewers would be able to answer them with high scientific quality. I wanted reports that were beyond reproach.

What questions did you ask?

Ms. Kappstein's case primarily concerned the obligation to wear masks, and whether wearing masks by laypeople in public spaces, in general and by children in particular, makes any sense. Kuhbandner's case concerned the harm masks can cause to children. Ms. Kämmerer's case concerned the validity of PCR tests and rapid tests. There is a differentiated order on the taking of evidence. The decision I made is published on openJur, where anyone can read it.

Have the courts or the Federal Constitutional Court studied or at least read these opinions?

I can't say for sure whether they read them. But so far, not a single court has examined the content of the expert opinions. Not even the Thuringian Higher Regional Court, which overturned my ruling. An appeal was then filed against that. The Federal Court of Justice in civil matters hasn't addressed them either. And the Erfurt Regional Court, which convicted me, hasn't addressed them either, nor has the Federal Court of Justice in the proceedings against me, nor the Federal Constitutional Court. Not a single court has evaluated the expert opinions. They said it wasn't necessary. I was merely accused of having commissioned expert opinions from a particular direction.

Weren't the expert opinions mentioned in the prosecution's pleadings?

Just mentioning in this context that my alleged bias is also reflected in the fact that I commissioned experts from a particular background.

So nobody looked into the content?

That's the curious thing: The selection of experts was one of the accusations leveled at me. But whether I could really be blamed for that could only have been determined by examining the content of the reports. But that wasn't the case.

You were accused of colluding beforehand. So that's not true?

What exactly does "snitching" mean? As far as we can tell, I was the first judge, at least in the German-speaking world, to ever obtain expert opinions. You can't just mail an order for evidence to any expert witness.

The reports are so important because they essentially reach the same conclusion as the RKI protocols. The courts should have taken that into account.

The expert opinions have been fully confirmed, if one takes what is now known after the publication of the RKI protocols as a benchmark. And the real problem is: People keep saying, yes, with today's knowledge, it's clear that the measures often don't stand up to critical scrutiny. But with the knowledge available back then, there was no other way; none of this was known back then. That's simply not true. The RKI was already aware of the crucial points from the beginning of 2020. The question arises: if this was known from the beginning, and if they not only could have known better back then, but even knew better, why were these measures ordered anyway? And for me, that is the central question that investigative committees, public prosecutors, and courts should actually be addressing.

So the expert reports at that time already had the same findings as the RKI?

Yes, the RKI already knew what the experts discovered back then, and today, practically everyone knows it. Unfortunately, as far as I can see, the judiciary has not yet used the publication of the RKI protocols to initiate a self-correction.

You were accused of bringing the parents in yourself and helping them prepare their application.

The parents were completely unknown to me. Three or four days before the suggestion was received, a friend who knew these parents—but I didn't!—sent me the parents' suggestion. He essentially asked me whether it was okay to submit it as is. I made a few minor editorial changes. For example, I noticed that it mentioned regulations from North Rhine-Westphalia, which aren't applicable in Thuringia. But basically, it wouldn't have mattered; a single sentence would have been enough as a suggestion. I could have initiated the proceedings without any suggestion at all.

I've been asked many times why I waited for such a suggestion. There's a good reason for that. I mentioned earlier that many parents approached me about whether and what could be done about the measures. I could have taken that as an opportunity, purely theoretically so to speak, to say, well, fine, then I'll initiate proceedings now. I don't have to wait for a suggestion. I can do it officially. But many parents have said they're afraid their children will be made fun of, that they might experience bad treatment at school if they don't wear masks.

I didn't want to impose such a procedure on children and parents who said: We don't agree with the measures, but rather than our child being bullied in class, we'd rather endure it quietly and angrily. I wanted parents who were fully committed to the procedure, and therefore waited until parents explicitly suggested it. It wouldn't have been legally necessary.

You were accused of being biased because you spoke to the parents.

It is explicitly stated in several commentaries in the specialist commentary on family law that not only the civil servant in the registry or the judicial officer, but also I myself as the responsible family judge may take up such a suggestion. And I am even supposed to ensure that the presumed wishes of the person making the suggestion are inquired about. And I am supposed to ensure that the request is clearly formulated. This is explicitly stated in the commentary. And the interesting thing is that the Federal Court of Justice (BGH) expressly acknowledged this to me in its decision. It said, yes, I was allowed to participate in the formulation of this suggestion and provide assistance. But, and now comes the thing the Federal Court of Justice (BGH) is accusing me of: I should have made a note of it. I failed to do that. And that is the accusation made by the BGH.

Not everyone can work as carefully as Ms. von der Leyen, who keeps meticulous records of every deal she makes. You issued the recommendation for two children from one family, but also for two classes, meaning multiple students.

If you look at it closely, there were two schools: a regular school and a primary school. I issued the order for those two children and all the children at both schools.

So you gave all children who wanted to do so the opportunity not to be subjected to the measures?

I didn't just obtain the expert opinions. I also appointed a legal representative, a lawyer, for these two children. The law stipulates that this can or even must happen in certain cases. This legal representative is a type of advocate for the children who must and should represent their interests. The lawyer provided me with a detailed report on the situation of the two children. Parts of it are also printed in my decision. The report made it clear to me that the situation is the same not just for these two children, but for all the children at these two schools. This prompted me to issue a decision by way of an interim injunction not only for these two original children, if I may call them that, but also for their classmates at both schools.

And this decision was made in such a way that they said, okay, anyone who still wants to wear a mask voluntarily and wants to get tested can do that?

An important point that has often been misreported. I didn't "forbid" children from wearing masks or getting tested, I only forbade them from being required to do so. Anyone who wanted to do so voluntarily could have continued doing so at any time.

Then you issued this order, what happened after that?

It wasn't implemented at all.

Oh. Why?

That's a good question. The ministry probably worked to prevent this from being implemented. Legal action was then taken.

But if you make a decision and it becomes legally binding, then we would have thought that people would have to abide by it until it is repealed.

Don't hold me to that; I can't tell you exactly whether it was implemented for half a day. As far as I know, my decision wasn't implemented at all. The Free State of Thuringia then filed an appeal, and the Thuringian Higher Regional Court then overturned my decision.

Among other things, they were accused of the fact that the administrative courts were competent to make such a decision and not a family court.

At the time of my decision, this was legally completely unclear. My decision was based on a specific statutory provision, namely Section 1666 Paragraph 4 of the German Civil Code (BGB), which allows me to make decisions that have effect against a third party. Who such a third party is—for example, in this case, the teachers and principals or the school administration—and whether or not I, as a family court judge, can issue such an instruction to them, was completely unclear at the time. Only now, through my case, is there higher court ruling on this matter.

So you made the decision. Who was it addressed to?

It went to everyone involved: to the parents who suggested it. It went to the two schools, to the Free State of Thuringia, to the lawyer who was appointed as the children's legal representative, and to the Youth Welfare Office.

A broad circle. Actually, anyone at school could have said: Here's a court ruling, no one needs to wear a mask here at all, right?

Yes, but that was not the case because, as far as I heard, the resolution was not implemented.

But that means someone must have told the parents and teachers, yes, you have a ruling from an independent judge, but it doesn't count. Right?

I can only speculate as to who exactly said what. In any case, the resolution was not implemented.

Within a week, the state of Thuringia filed a complaint.

This left the schools in the clear. They said, "Here's a complaint, we have nothing more to do with it."

Next came the house searches?

The first house search, of which I've had two, came pretty quickly. That was in April 2021, and then there was a second one in June 2021. The decision was made on April 8, and the house search took place on April 26, just two weeks later.

How did it go? They were at your front door early in the morning. How many police officers were there? Were they masked?

They weren't masked, but there were quite a few of them. A prosecutor was there, as were several police officers. They showed the search warrant and then searched my apartment, my office, and my car.

What did you think back then?

I was completely surprised. I had expected that my decision would be discussed, and above all, that a discussion would begin on the merits, and that people would discuss whether these measures could be maintained. But I never would have expected that an investigation would be launched against me.

What was your reaction?

I was alone during the house search, and I was shocked and completely astonished, and I had to take it all in. I only learned at that moment that an investigation was underway against me. You don't have a quiet moment to digest it either, because the search is going on all around you.

Did they completely turn the apartment upside down or politely ask for the computer?

Well, they behaved fairly civilly, I can say that, but they were looking for all sorts of things: I had the impression that they knew on the surface what they were looking for—phones, computers—but that, deeper down, they didn't really know exactly what they were looking for.

Did you talk to the police about this, or are you just assuming it was because of the context?

Well, for example, I saw them pull a piece of paper out of my wastebasket. I had written down a paragraph, just this paragraph, I don't remember in what context. I've been doing this for decades; I was probably thinking about something and making a note. And then they look at the piece of paper and decide, is this a lead or not? That showed me that they don't really know what to look for.

Then you left again with your computers?

My work computer, which isn't at my home, but at the office. Of course, it was searched as well. A group of officials and prosecutors searched my office. They also looked at my work computer, of course.

It was claimed that there was nothing left on your private computer because you had installed a new operating system on it.

That's not true. The computer I had back then was already ancient and wouldn't have accepted a new operating system. It also wouldn't accept software updates. And then it broke, so I replaced it. Well, it wasn't a new operating system, but a new computer—a new laptop, to be precise. It also had a new operating system, of course.

What happened next?

I continued to work full-time until January 2023, about another year and a quarter, with the same responsibilities in my department. It was only in January 2023 that I was provisionally suspended from duty.

You were suspended after the entire pandemic was already over? After everyone had already learned a completely different lesson?

I can only speculate that the investigation dragged on so long because the public prosecutor's office was so busy evaluating their data. There were also searches of the homes of a colleague, the parents, the experts, and numerous other individuals. And, of course, that involves a lot of computers, cell phones, and other things. The lawyer who acted as legal counsel for the children also had her home searched.

Is it actually okay to act like this with a lawyer?

Well, I don't think that's okay. I've already said, I don't know what they were actually looking for. My lawyer, Dr. Strate, once said that the only "instrument" I had used to commit the crime was the resolution I passed. And you don't have to search for it; it's in the file. They should have just looked at it.

You were then convicted, and the appeal and the Constitutional Court also dismissed practically everything in the final instance, right?

I was convicted in the first instance in August 2023. There is no appeal against this decision; instead, we have filed appeals with the Federal Court of Justice. On November 20, 2024, the Federal Court of Justice announced its decision, dismissing our appeal and that of the public prosecutor's office.

And now you're finally out of service, have lost everything, your pension, your benefits, everything?

With the announcement of the Federal Court of Justice's decision on November 20, 2024, my conviction, which had previously been handed down by the Erfurt Regional Court, became final. I am therefore no longer a judge, nor am I a retired judge, but no longer a judge at all. I also no longer receive any salary. I have completely retired from the judicial service.

How do you live now?

From the support of friendly people around me. I'm not allowed to work as a lawyer either. I don't have a bar license and wouldn't get one for years. I'm also not allowed to run for election for any party, no matter which one. It's a side effect of my conviction that I'm not allowed to hold such an office for, I believe, five years. So, I'm somewhat handicapped in that regard.

Yet you don't seem bitter, but friendly, cheerful, and balanced. Is this all just an act, or do you have something up your sleeve that says you can handle the situation?

This isn't a show. These have been very, very stressful years for me. But at the moment, I'm coping and am happy that there are people who support me. That gives me stability.

Do you feel socially ostracized or do you see yourself as a quiet hero?

I don't see myself as a hero, nor as a silent one. I was just trying to do my job. I'm aware of the social divide, but I don't have anything special to say about it. Millions of other people in Germany, and not only in Germany, can tell the same story.

Do you actually still have a chance of taking legal action, perhaps at the European level?

We still need to discuss and consider this. There is a path to the European Court of Human Rights, the ECHR.

Would you make the same decision today as you did back then, knowing everything that happened to you afterwards?

I would do the same as back then, namely examine everything carefully and then make a decision. There are also differences compared to the situation back then. Today, there is higher court jurisprudence, for example, regarding actual or presumed jurisdiction. That didn't exist back then.

Note for listening: The following video contains the reasoning of the Federal Court of Justice. It becomes clear that the Federal Court of Justice has adopted the narrative of the lower courts that the judge's actions were some kind of insidious conspiracy. At no point does the Federal Court of Justice mention the content of the expert opinions, let alone the findings from the RKI files. The Federal Court of Justice insinuates the possibility of a ruling in a vacuum, discredits the experts without any factual basis ("one expert had previously expressed criticism"), and ignores the fact that at the time of the decision, public debate about the measures was suppressed by politicians, in some cases using brutal methods ( "panic paper" from the Ministry of the Interior ). The Senate of the Federal Court of Justice maintains the in no way substantiated possibility that the judge was not at all interested in the child's welfare. Ultimately, it sides with the Free State of Thuringia, which suffered disadvantages as a result of the judge's suggestion. The Federal Court of Justice does not explain what these disadvantages consisted of. The impression arises that the judicial authorities in these proceedings – notwithstanding their obligation to neutrality, which they pathos-reminded the judge of – wanted to give priority to the unconditional enforcement of state measures, even “ex post” and without considering relevant, new findings.

Do you have feedback? Write to us! [email protected]

Berliner-zeitung