Alzheimer's blood test could 'revolutionise' diagnosis

More than 1,000 people across the UK with suspected dementia are to be offered a blood test for Alzheimer's disease which it is hoped could revolutionise diagnosis of the disease.

The blood test can detect biomarkers for rogue proteins which accumulate in the brains of patients with the condition and will be used in addition to pen and paper cognitive tests, which often misdiagnose it in its early stages.

Scientists leading the trial at University College London believe the blood test will improve the accuracy of diagnosis from 70% to more than 90% and want to see how that helps patients and clinicians.

Patients will be recruited at 20 memory clinics as part of the study, which aims to see how well the test works within the NHS.

Alzheimer's disease is the most common form of dementia and is associated with the build-up in the brain of two rogue proteins - amyloid and tau - which can accumulate for up to 20 years before symptoms emerge.

The new blood test, which costs around £100, measures a biomarker called p-tau217, which reflects the presence of both proteins.

Previously, the only way to confirm Alzheimer's was by specialist PET brain scans and lumbar punctures to extract cerebrospinal fluid.

However, these "gold standard" tests are not part of routine Alzheimer's diagnosis and only 2% of patients ever receive them.

Professor Fiona Carragher, chief policy and research officer at the Alzheimer's Society, said: "Our recent Lived Experience Survey revealed that only a third of people with dementia felt their experience of the diagnosis process was positive, while many reported being afraid of receiving a diagnosis.

"As a result, too often, dementia is diagnosed late, limiting access to support, treatment and opportunities to plan ahead."

Now, the Alzheimer's Disease Diagnosis and Plasma p-tau217 (ADAPT) trial has begun recruitment at a memory clinic in Essex, with 19 additional specialist NHS centres planned to be involved across the UK.

The study is being led by scientists at University College London, and is supported by Alzheimer's Research UK, the Alzheimer's Society, with funding from the People's Postcode Lottery.

Jonathan Schott, professor of neurology at University College London and chief medical officer at Alzheimer's Research UK said he was "thrilled" to welcome participants onto the ADAPT trial.

He described the trial as "a critical part of the Blood Biomarker Challenge, which we hope will take us a step forward in revolutionising the way we diagnose dementia."

Half the participants in the study will receive their blood tests results within three months while the others will be told after 12 months.

The study team will establish whether providing results earlier helps speed up diagnosis, guides decisions about further investigations, and influences how both patients and doctors interpret and respond to the results.

The impact of blood test results on quality of life will also be measured.

If the trial is deemed successful, the blood test could become a standard part of Alzheimer's diagnosis. This will be crucial in years to come as a raft of new drugs to combat early-stage disease are in the final stages of clinical trials.

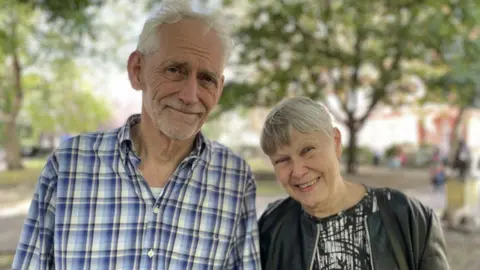

Steven Pidwell, 71, from north London, says an accurate, rapid blood test for Alzheimer's, combined with new treatments, would be a "gamechanger" for families affected by the condition.

His partner of more than 50 years, Rachel Hawley, was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease almost a decade ago.

Steven told the BBC: "I think it would mean everybody's idea of Alzheimer's would change. We would treat Alzheimer's more like having a disability, rather than sort of a curse, and something we can't talk about."

A diagnosis of Alzheimer's can be devastating but the couple say they refuse to let the disease spoil their time together.

Rachel, 72, said: "I think I still have a very happy life, and am very lucky in all sorts of ways."

The couple were part of a group of patients with lived experience of Alzheimer's, who helped researchers at UCL design the trial and the feedback to potential volunteers.

The team at UCL expect to have results in around three years.

BBC