Carney wants to fast-track LNG expansion in B.C., but can Canadian natural gas compete globally?

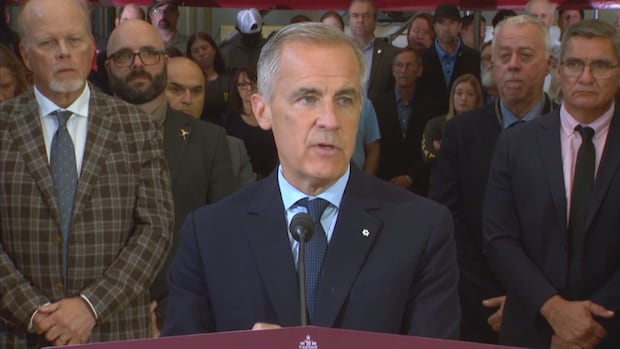

When Prime Minister Mark Carney included a Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) project on his list of the first five "major projects" his government would help fast-track, it wasn't just opponents of the fossil fuel industry that raised their eyebrows.

Energy policy analysts have raised doubts about the decision and say the important question to ask is what has stopped phase two of LNG Canada moving forward.

"It's actually had all of the approvals it needs for nearly a decade," said Amanda Bryant, senior analyst on the oil and gas team at energy and climate policy think-tank the Pembina Institute.

"The uncertainty, I think, is actually coming from the global market. And from it not being clear what the business case is or how strong the business case is for Canadian LNG."

While announcing the projects on Wednesday, Carney said the terminal expansion "will directly help our country transform into an energy superpower."

"It will diversify our trading partners, help meet global demand for secure, low-carbon energy, and support tens of thousands of new high-paying careers," he said.

But in addition to concerns from analysts about the viability of energy markets, climate advocates also note that doubling down on liquified natural gas, a fossil fuel that's less polluting to burn than coal or oil but a fossil fuel nonetheless, jeopardizes climate goals in both B.C. and Canada, and sends a negative signal to the rest of the world.

"It produces lots of emissions both in the production and transport of the gas with methane leaks and all the rest of it," said Tim Gray, executive director of the advocacy group Environmental Defence.

At the moment, almost all of LNG Canada's oil and gas is exported to a single market: the U.S.

But in June, LNG Canada started producing liquefied natural gas for export at its facility in Kitimat, B.C., about 650 kilometres northwest of Vancouver. The plant will receive natural gas, transported via the Coastal GasLink pipeline from near Dawson Creek in B.C.'s northeast, cool it, and ship it to Asian markets.

The road to bring LNG Canada online was long and fraught, especially with years of protests and legal challenges over the Coastal GasLink pipeline.

The pipeline's owner, TC Energy, says including LNG Canada on the major projects lists "reflects the essential role energy infrastructure plays in Canada's economic sovereignty and energy security."

When the first tanker left the LNG Canada export terminal in June this year, it was seen as a major step for Canada's LNG industry and its efforts to find new customers overseas.

B.C. Premier David Eby hailed the $40 billion that's been committed by a consortium of foreign companies to build the export terminal, and said the project would contribute 0.4 per cent to Canada's GDP once fully operational.

He also celebrated the 65,000 people who have found work at the project and the connected pipeline over its six-year construction period.

But independent energy and climate policy groups have long raised doubts about the economics of the project.

"Canada's LNG is actually not very cost competitive," said Pembina's Bryant. "It's about $24 US per tonne of LNG compared with a global average of about $15 US per tonne of LNG. And so it's going to be tough for Canada to compete on a cost basis."

Another major independent think-tank, the Canadian Climate Institute, reacted this week to the LNG Canada announcement by warning that the "prospect of fast-tracking oil and gas projects, including LNG, without mitigating emissions impacts through electrification or other means, represents a risk to Canada's emissions goals."

The International Institute for Sustainable Development, another policy group based in Canada, has suggested that the LNG Canada expansion is financially risky because without substantial government subsidies, it will struggle to compete with cheaper gas from other countries.

Bryant also notes that while a lot of jobs are created during construction and the initial phases of the project, they're usually temporary and don't last over the long-term operation of the project.

A potential carbon bombThe B.C. government has set a goal of net-zero emissions by 2050, and an interim target for 2030. A government report shows the province is already on track to miss that target — without the added emissions from an LNG expansion.

The pipeline and terminal carry gas from the Montney formation, an area of 130,000 square kilometres in northern B.C. and Alberta.

The Montney is a major resource, and a 2022 study published in the journal Energy Policy labelled it as a carbon bomb — a fossil fuel megaproject that, if fully exploited, could end up adding billions of tonnes of carbon to the atmosphere and having an outsize impact on global warming.

Expanding LNG Canada could have impacts for both the global climate as well as Canada's own domestic emissions reductions targets.

Though the emissions that result from using the gas mostly won't count against Canada's totals — that will happen in the foreign countries that buy it — it's estimated that burning all of the Montney's reserves will lead to 13.7 billion tonnes of CO2 emissions, according to the study.

Liz McDowell, senior campaigns director at environmental group Stand.Earth, says an expanded LNG Canada would put B.C.'s climate targets out of reach.

She says if phase two goes ahead, LNG Canada's emissions could reach 10 per cent of B.C.'s total emissions.

The facility has already backed away from plans to use only clean electricity in its phase two expansion, and emissions from operations at the LNG terminal (liquefying and processing the gas), do count toward Canada's totals.

A better bet, she says, would be to continue to grow renewable energies like solar and wind.

"I just look at it and say, 'Why are we choosing to prioritize this sort of project when there's so many better projects in front of us?' " said McDowell.

"As the world transitions to green energy, we're going to get left behind."

cbc.ca