Sharks freeze when you turn them upside down

For some animals, this freezing response (called “tonic immobility”) can be lifesaving. Australian possums have been known to “play dead” to avoid predators. Rabbits, lizards, snakes, and even some insects do it, too.

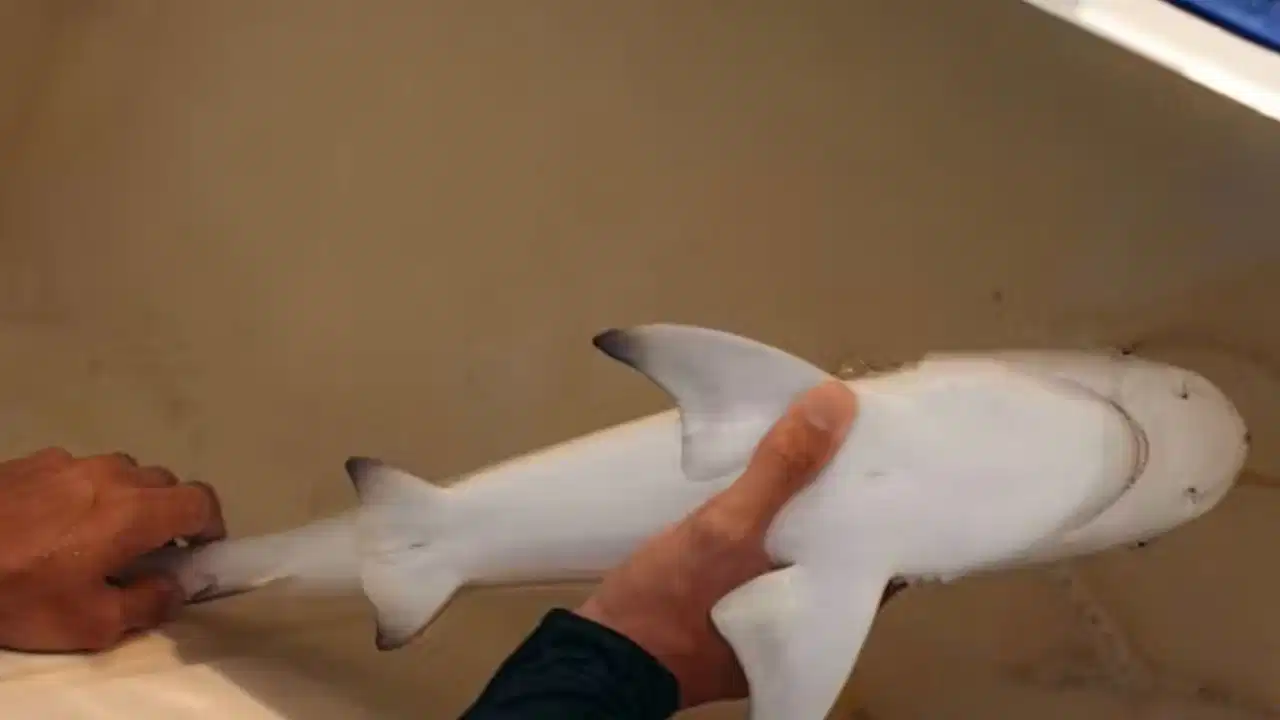

This strange behavior is also seen in sharks, rays, and their relatives, Popular Science reported. In this group, tonic immobility is triggered when the animal turns upside down; it stops moving, its muscles relax, and it enters a trance-like state. Some scientists even use tonic immobility as a way to safely hold certain species of sharks.

So why does this happen and does it actually help these marine predators survive?

The mystery of the 'freezing shark'Although well known in the animal kingdom, the reasons behind tonic immobility remain unclear, especially in the ocean. It is generally thought to be a defense against predators, but there is no evidence to support this idea in sharks, and alternative hypotheses exist.

We tested 13 species of sharks and rays, and one species of chimera (a relative of sharks commonly called the ghost shark) to see if they would enter tonic immobility when gently turned upside down underwater.

Seven species got in, but six didn’t. We then used evolutionary tools to identify this behavior across hundreds of millions of years of shark family history, and analyzed those findings.

So why do some sharks freeze?

Three basic hypothesesThere are three main hypotheses to explain tonic immobility in sharks:

- Strategy against predators: ‘Playing dead’ to avoid being eaten

- Role in reproduction: Some male sharks turn females upside down during mating, so tonic immobility may help reduce fighting

- Sensory overload response: A type of shutdown during extremely high stimulation

The results do not support either of these explanations.

There is no strong evidence that sharks benefit from freezing when attacked. In fact, modern predators such as killer whales can use this response against sharks by turning them upside down to immobilize them and then extracting their nutrient-rich livers – a deadly exploitation.

The reproductive hypothesis is also inadequate. Tonic immobility does not differ between the sexes, and immobility may predispose females to harmful or forced mating activities.

What about the sensory overload idea? It hasn't been tested or confirmed. So we propose a simpler explanation. Tonic immobility in sharks is probably an evolutionary relic.

A case of evolutionary baggageOur evolutionary analysis suggests that tonic immobility is “plesiomorphic”—an ancestral trait likely found in ancient sharks, rays, and chimeras—but as species evolved, many lost the behavior.

In fact, we found that tonic immobility was lost at least five times independently in different groups, which begs the question, “Why?”

In some environments, freezing can actually be a bad idea. Small reef sharks and bottom-dwelling rays often squeeze through narrow crevices in complex coral areas while feeding or resting. Relaxing in such environments can get them stuck or worse. This means that losing this behavior may actually be advantageous in these lineages.

So what does all this mean?

Rather than a clever survival tactic, tonic immobility may simply be “evolutionary baggage,” a behavior that once served a purpose but persists in some species because it no longer causes enough harm to be selected against.

A beautiful reminder that not every feature in nature is compatible. Some are just oddities from history.

The study helps challenge long-held assumptions about shark behavior, shedding light on the hidden stories of evolution still at work in the deep ocean. When you hear a shark “playing dead,” remember that it could just be muscle memory from a long, long time ago. For some animals, this freezing response (called “tonic immobilization”) can be lifesaving. Australian possums have been known to “play dead” to avoid predators. Rabbits, lizards, snakes, and even some insects do it, too.

Cumhuriyet