Annelid endemic to Mexico contributes antibacterial molecule

Annelid endemic to Mexico contributes antibacterial molecule

It is capable of inhibiting the growth of a very common pathogenic microorganism in hospital infections.

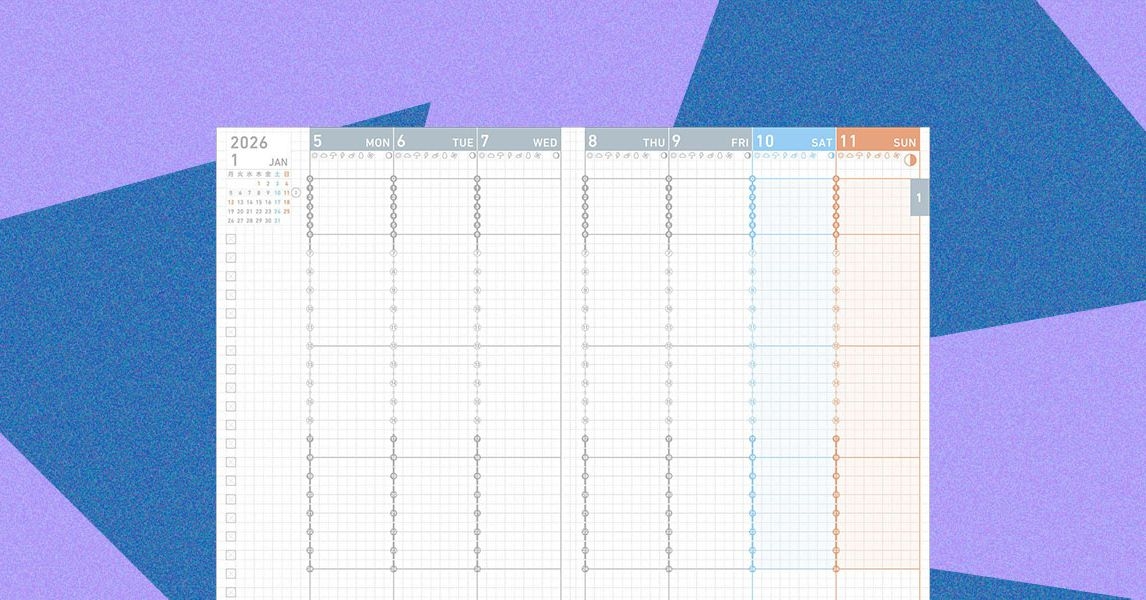

▲ Leech samples collected in the country and kept at the Institute of Biology of the UNAM. Photo by Cristina Rodríguez

Eirinet Gómez

La Jornada Newspaper, Tuesday, November 11, 2025, p. 6

A bacterium found in a leech endemic to Mexico could help us fight antibiotic resistance, reported researcher Deyanira Pérez Morales, from the Center for Genomic Sciences of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, whose headquarters are located in Cuernavaca, Morelos.

“In leeches, we find a bacterium of the genus Chryseobacterium that produces compounds with antibacterial activity. Interestingly, it inhibits the growth of Staphylococcus aureus , a very common pathogenic bacterium in hospital infections that already shows resistance to multiple antibiotics,” he noted.

In an interview with La Jornada , Pérez Morales explained that antimicrobial resistance, "the loss of effectiveness of medications (antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals) to combat infections," constitutes a relevant public health problem worldwide.

He added that the excessive and improper use of these drugs in both humans and animals has caused pathogens to become resistant, and mentioned that it is a serious situation because we are running out of therapeutic options to treat infectious diseases.

“There have already been reports of people dying because they were infected with bacteria resistant to all antibiotics available on the market,” he warned.

This health emergency led her to focus her scientific work on searching leeches for new molecules with antibacterial activity. “All animals live in symbiosis with millions of bacteria in our bodies, but leeches are different; they have very few species in their microbiota,” she explained.

Under that hypothesis, "their bacteria could produce compounds that prevent the growth of others."

The researcher collected specimens of Haementeria officinalis in the lagoon of the municipality of Coroneo, in Guanajuato. Once in the laboratory, she extracted the contents of the crop, a part of the intestine, identified about 40 species of bacteria, and then focused on 10.

He then cultured these bacteria in specific media and tested them against pathogenic bacteria using an inhibition assay (a laboratory test). When a leech bacterium successfully inhibits a pathogenic bacterium, an “inhibition zone” forms—a visible area where the harmful bacterium cannot grow.

To identify the bacteria taken from the leeches, they extracted their DNA and amplified the 16S gene, a test that allows them to determine which genus each one belongs to; this is how they found Chryseobacterium , which showed antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus , a bacterium that can cause a wide variety of diseases.

“The most interesting thing is that it inhibited clinical strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ,” the academic highlighted.

These strains are listed by the World Health Organization as priority pathogens for research and development of new antibiotics. “It is urgent to find new molecules that inhibit the growth of these resistant strains,” stressed Pérez Morales, for whom this discovery is significant because it revives an ancient practice: “the medicinal use of leeches in countries like Egypt or Greece” from a modern perspective.

“In this case, we are talking about using a natural resource from Mexico, the endemic leech, in which an antibacterial molecule has been identified,” he emphasized.

Based on this discovery, Pérez Morales, along with his master's student Brianda Hernández, is now working to isolate the molecule to study its cytotoxicity, first in laboratory larvae and in the future in human cells.

“This step is crucial if we want to test it as a new molecule to combat infectious diseases in humans,” the scientist explained.

One possible additional use, he added, would be as a disinfectant to help eliminate antibiotic-resistant bacteria on surfaces or on farms where long-lasting pathogens have also been detected.

"If its effectiveness and safety are confirmed, this molecule could open a new path in the fight against antibiotic resistance," he concluded.

An unexpected ally in understanding our brain

Eirinet Gómez

La Jornada Newspaper, Tuesday, November 11, 2025, p. 6

The leech has become an unexpected ally in understanding how the human brain works. Its neurons, which share similar mechanisms and genes with ours that have been maintained throughout evolution, allow us to observe live how serotonin, a key neurotransmitter that regulates mood, sleep, emotions, and attention, is released.

José Arturo Laguna Macías, a doctoral student in biomedical sciences at the Institute of Cellular Physiology of UNAM, explained that through these invertebrates they have been able to study step by step the complex process by which neurons communicate and better understand how brain activity is organized.

In an interview with La Jornada , he explained that they used leeches in this research because they share small, functional "parts" in common, such as ion channels that allow the passage of molecules, calcium sensors, and vesicle fusion machinery, among others.

Serotonin release

The leech's nervous system, unlike ours and that of mammals, is segmented into 21 ganglia connected by nerve cords that run from the animal's head to its tail, like a string of beads. Each ganglion contains 400 neurons with a stereotyped distribution, making it easy to distinguish a pair of large, serotonergic Retzius neurons (named after their discoverer, Gustaf Retzius).

“These neurons are ideal for observing how serotonin is released from the soma (the neuron's body) because we can extract them and keep them in culture, stimulate them, record their activity, and inject solutions while observing them under a microscope.”

Initial laboratory work has allowed them to map this release pathway from the soma and its key components, which depends on calcium and requires the mobilization of its components. Lagunas Macías is now focused on identifying the proteins that execute the release of serotonin from the somatic membrane.

“Proteins are like tools that the cell manufactures from a gene, and each one performs a specific task, for example, detecting calcium, moving vesicles, joining membranes. The next step is to move from the level of tools to that of instructions: to find out which genes and which signaling pathways coordinate each stage of the process and when they are turned on or off in response to different signals,” he explained.

Defining this type of neuronal communication, the researcher mentioned, allows us to understand how the brain regulates its state and perceives the world.

jornada