Education in Colombia, amid serious setbacks, questionable indicators, and some notable achievements in three years of government

On several occasions, President Gustavo Petro has named education as the top priority during his administration. To prove his point, he has not only echoed the resources allocated to the sector (the highest in the General Budget of the Nation - PGN) , but also alluded to various goals, most recently, new spaces in higher education. However, according to experts consulted by EL TIEMPO, after three years, the debts outweigh the progress in the sector.

Former Bogotá Education Secretary Edna Bonilla believes this: "There have been many promises regarding educational change, some achievements that I think must be acknowledged, but above all, there are significant debts owed to the education sector."

A recent example is the goal of 500,000 new places in higher education, which, according to government calculations, will have already reached 190,000 places created by 2024, a figure disputed by various analyses. This is because the data, published in the National Higher Education Information System (SNIES) , show that undergraduate places have actually grown by 125,000 (if the first-year indicator is taken into account, that is, only first-time students) or 62,000 (if the total enrollment indicator is taken into account).

But analysts consulted by this newspaper maintain that there are many other debts with education. While it's true that there have been significant advances in the last three years (such as the law on free higher education, or the increase in PAE coverage and the immediate transition rate to higher education), many other problems have worsened.

For Gloria Bernal, director of the Educational Economics Laboratory (LEE) at Javeriana University , a large part of the problem stems from the budget. While it has reached its highest levels, the percentage dedicated to investment is decreasing.

"Most of the budget increase is going to operating expenses, which include salaries, benefits, rent, etc. In investment, which goes to infrastructure, laboratories, quality improvement, etc., the budget has been significantly reduced ," he stated.

Of the 79.2 billion pesos allocated for education this year, only 8 billion pesos are allocated for investment, or 10.1 percent . This is not only a percentage lower than the 11.9 percent allocated in 2024, but also nominally lower than the 8.3 billion pesos allocated in that year. This decline has been present throughout the government and could be repeated in 2026 if the proposed National Development Plan (PGN) submitted to Congress remains unchanged.

This is reflected, for example, in the goal of new university campuses. Part of the improvement in coverage is due to the "College-University" strategy, which seeks to leverage school infrastructure to offer undergraduate classes (and which has been applauded even by government critics). The problem is that this is very different from the promise to create 100 new universities and university campuses (something President Petro insisted on).

For education analyst Francisco Cajiao, "that's clearly not what happened. If they didn't do it in the first three years, they won't do it now, especially with the enormous fiscal deficit the state is facing."

According to Bernal, progress in this area "has been minimal," while Bonilla questions the government's narrative regarding this goal: "There is enormous opacity in the indicators for monitoring. It is not known whether the Ministry of Education is referring to 100 campuses, 100 universities, or 100 other projects. What one observes is that this goal has not been met." This, experts maintain, could lead to the rhetorical claim that the goal has been met, but there would be no way to verify it. What is clear, they say, is that strictly in terms of infrastructure, progress is poor.

Regarding higher education, two other issues are causing concern in the sector, both related to policies and decisions originating from the Executive Branch. The first is the elimination of subsidized credit lines from Icetex , which led the institution to benefit from 50,000 new users per year to only 10,000 by 2025. This does not include the elimination of interest rate subsidies for more than 200,000 users, who have seen their bills increase by up to 100 percent.

Icetex announced it will suspend interest rate subsidies. Photo: Montage based on photos from Istock and Icetex

Cajiao described this as "a terrible mistake that has closed the doors to many people who cannot enter public universities because they simply don't have the capacity to accept them, even if the government insists otherwise."

These benefits primarily benefited people in social classes 1, 2, and 3 (90 percent of the institution's users). Analysts consulted believe that, while this does not mean the disappearance of Icetex, it is a reduction to its minimum expression, affecting the economic stability of private universities and, above all, leaving unprotected a population that requires these loans to access higher education.

The second controversial issue is the government's role in the internal governance of higher education institutions. Evidence of this is the controversy over the rectorship of the National University (where the election of Ismael Peña was reversed and Leopoldo Múnera was later appointed, all fueled by the actions of the then Minister of Education, Aurora Vergara, and her representatives on the Higher Council). This controversy is awaiting a final decision from the Council of State.

But disputes over rectorships are repeated at several other universities, such as the Technological University of Chocó, the University of the Atlantic, or, recently, at the Popular University of Cesar (where a recent investigation by *El Colombiano* alludes to interests of Chief of Staff Alfredo Saade, Interior Minister Armando Benedetti, and the Ministry of Education, Daniel Rojas).

According to Edna Bonilla, “the governance of public universities is a particular concern. It is regrettable that last week, preventive measures and special surveillance measures were announced for the University of Antioquia (which is facing a major financial crisis, which led to several payroll defaults last year), adding to what has happened at the National University.”

He added: "If this is happening with the National University and the University of Antioquia, what can we expect from other institutions in much smaller regions? One would dare to say that a path of new interventions is surely on the way."

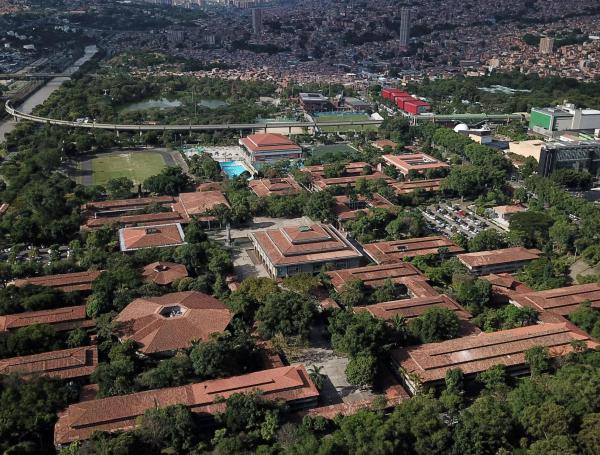

University of Antioquia campus in Medellín. Photo: University of Antioquia.

All of the above has been covered in the media in recent years, but for experts, what's truly worrying is what's happening in primary and secondary education, that is, in schools. Cajiao explains: "This is really my greatest concern, because higher education, ultimately, is defending itself, but primary education, which is where children and adolescents are, does have serious problems."

The indicators are not good. During the Petro administration, net enrollment (of children aged 5 to 16 who, due to their age, should be studying) has only fallen, reaching 90.3 percent in 2023 (latest available data), compared to 91.5 percent in 2022 and 92.3 percent in 2021. In a system with nearly 10 million students, that 2 percent decrease means nearly 200,000 fewer students in two years and 926,000 children without schooling.

But that's not the only concern. The dropout rate reached its highest levels in 2022 and 2023 (4.4 percent and 3.9 percent, respectively), while grade repetition, which historically averaged around 2 percent, reached 6.7 percent in 2022 and 9.2 percent in 2023 (the highest figure in history).

All of this speaks not only to inequality but also to quality issues, as the director of LEE explains: “Reading levels nationwide are worrying. Grade repetition has increased, and part of this indicator is because children have been experiencing learning gaps since the pandemic. Nothing was ever done to remedy this; it hasn't been a priority. This doesn't even include the almost nonexistent efforts in early childhood education.”

The seriousness of this problem, which, although long-standing, is experiencing setbacks under this government, is because "this is where the greatest social gaps are generated, and this has been abundantly demonstrated by all the studies conducted in the last two decades," explains Cajiao.

MATEO CHACÓN ORDUZ | Education Deputy Editor

eltiempo