Valencina, the gigantic monumental complex led by women 5,000 years ago

Copper Age society has always been very difficult to study because, until a few years ago, there were hardly any human bone collections available to examine its demographics and social organization. However, the improved availability of evidence and the technical advances applied to the Valencina megasite (Seville), covering more than 400 hectares, have radically changed the picture. Now, Leonardo García Sanjuán, Professor of Prehistory at the University of Seville, and anthropologist Timothy Earle, from the Department of Archaeology at Northwestern University (United States), have managed to reconstruct with greater precision the social and political context of that period in the prehistory of the Iberian Peninsula, during which enormous " monumentalized central sites emerged that attracted large contingents of people, probably thousands," and where "a distinctive female leadership emerged, reflected in luxury objects made from exotic raw materials." This is according to their study , "Valencina, a Copper Age Political System," published in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. This spectacular "social world built around Valencina as a monumentalized central site came to a rather abrupt end around 2300 BC, after which a different social milieu began: the Bronze Age."

Between 3200 and 2200 BC, the Iberian Peninsula experienced a crucial historical period known as the Copper Age or Chalcolithic. During this period, a social organization emerged for the first time, centered around large monuments, "largely in the form of megaliths and ditched enclosures, which united people, creating and maintaining a sense of belonging and cooperation," according to the study.

Five thousand years ago, Valencina dominated the mouth of the Guadalquivir River, which, at that time, emptied into a large bay in the Atlantic Ocean. It was therefore in a privileged geographical location between Europe and Africa, at a time when long-distance trade was increasing across Eurasia, the Mediterranean, and North Africa. Valencina was contemporaneous with such important sites as Los Millares (Santa Fe de Mondújar, Almería) and Stonehenge (England).

Between 1860 and 1918, the first two tholos (La Pastora and Matarrubilla, funerary structures with long corridors and circular chambers) at Valencina were discovered, although it wasn't until 2010 that scientific research on this enormous site really took off. Since then, several scientific articles have boosted its international visibility. The scale and uniqueness of Valencina make it the "largest prehistoric site on the Iberian Peninsula, and one of the largest in Europe," covering more than 400 hectares, although it could reach 900.

The site is home to dozens of megalithic structures, enormous pits, hypogea (artificial caves), wells, and thousands of holes. The megalithic monuments and pits are often notable and include the aforementioned thols , such as Montelirio, La Pastora, and Matarrubilla. These feature corridors between 30 and 40 meters long and chambers up to five meters wide, with terracotta vaults or corbels between 2.5 and 4.5 meters high. Some pits are between nine and 10 meters wide and the same depth. “Geophysical studies carried out over the last 10 years at the northern and southern limits of the site,” both experts note, “suggest that some could have been hundreds of meters long (or even several kilometers), perhaps forming impressive concentric enclosures.”

Valencina is also notable for its sometimes unique, sumptuous objects, which are mainly found in direct association with individual burials, such as that of The Lady of Ivory (named after the rich trousseau with which she was buried) or with extraordinary individual garments worn by the powerful women of Montelirio, placed in a collective burial.

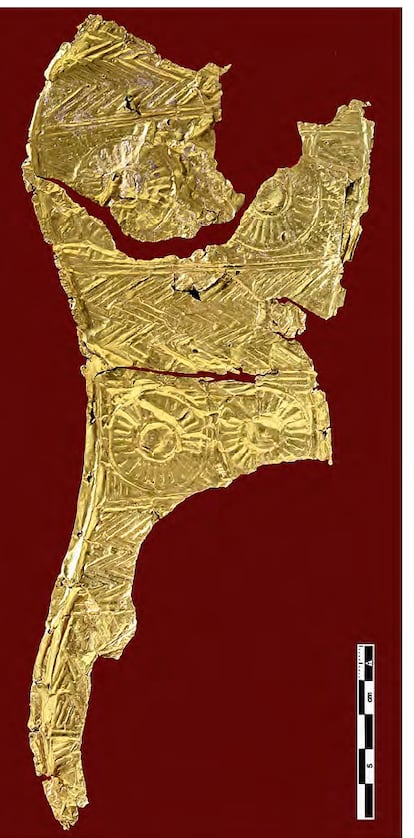

“The mastery employed in the manufacture of these remarkable, sumptuous and prestigious artifacts is impressive. These include ivory craftsmanship unparalleled for the period, a series of exceptional mylonite arrowheads with long appendages, objects crafted from rock crystal, as well as unparalleled dagger blades and arrowheads, amber beads and figurines, complex attire made from tens of thousands of seashell beads, a sophisticated—and probably sacred—gold foil decorated with four oculus motifs, extensive use of cinnabar, as well as numerous copper artifacts, including several spearheads, of which very few analogues exist in Iberia,” the study states.

The extraordinary value and uniqueness of this constellation of exuberant material culture was intended, in part, to mark and distinguish certain individuals and, in part, to celebrate a shared worldview. What was studied in Valencina can help us understand the processes that led its inhabitants to create early social complexity, but not to the point of forming a state.

The two professors therefore believe that Valencina was a political, religious, and economic system that attracted labor for the construction of monuments and acted as a market and supply center, centralizing the production of certain artisanal goods, as well as imports and exports. All of this benefited them from the ideological and religious capital concentrated in the sanctuaries or temples they built. "It would have been a balanced political system, financed by basic products and wealth, both probably backed by religious prestige," they say.

According to the hypothesis proposed in this paper, before the emergence of cities and states, central sites like Valencina served to provide cohesion to society, articulating its political and religious organization, with the construction of monuments playing a vital role. "The construction of these enormous monuments entailed considerable expense, thereby consuming the agricultural surplus produced by these communities," explains García Sanjuán. Essentially, therefore, according to this proposal, Late Neolithic and Chalcolithic monumentalism constituted a system of "burning" (or large-scale consumption) of surpluses to prevent them from falling into the hands of greedy leaders or elites and thus generating acute social inequalities.

In Valencina, around 3000 BC, geostrategic, geographic, and demographic conditions combined to allow for the development of "a strong material cultural personality, as well as forms of leadership that have not been found anywhere else of its time."

The power exercised by its leaders—mainly male and female—was unstable and, to a certain extent, fragile. Its peak occurred between 2900 and 2650 BC. From 2350-2300 BC, the site experienced an abrupt and steep decline and was finally abandoned. The second major crisis it suffered was aggravated "by the environmental effects of the so-called climate event 4.2, 4,200 years ago, which marked the end of the site's long history. This climatic episode, which manifested itself in the Mediterranean with increased aridity and drought, appears to have caused a concomitant sociocultural collapse throughout the macroregion." Valencina, as a central and attractive location for non-local people and foreign goods, ceased to exist.

Thus ended the fundamental role of these monumentalized central sites on the Iberian Peninsula after 2,000 years of existence. Over time, the disappearance of central Neolithic and Chalcolithic megasites, such as Antequera (Málaga) and Valencina, paved the way for the emergence of a new sociopolitical world. But that is a different story in the political economy, society, and culture of the world. It is known as the Bronze Age.

EL PAÍS

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fa73%2Ff85%2Fd17%2Fa73f85d17f0b2300eddff0d114d4ab10.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2Ff5d%2Ff4a%2F58e%2Ff5df4a58eddd11966927b0ac162b13ff.jpg&w=1280&q=100)