Who is Yeison Mestizo, one of the most delirious characters in 21st-century Colombian literature?

Let the Worst Pass , the new novel by Antonio García Ángel, hides a character who could become a recurring theme in Colombian literature classes for the next hundred or two hundred years. Yeison Mestizo is as disconcerting as Remedios la Bella and as full of mysteries and silences as Maqroll the Gaviero. Who the hell is Yeison? What makes him so special?

García forbade me from revealing a single word of the great secret of his novel, "You're screwing her, listen, you're screwing her, you can't give that spoiler , please!" And the word "spoiler" isn't free. Revealing Yeison's secret is like revealing that 007 dies in the final scene of No Time To Die under a hail of missiles.

Let the Worst Happen, by Antonio García Ángel Photo: Fernando Gómez Echeverri

“I think it's my most pop novel,” says García. And it's not just pop. It's a novel to devour with an extra-large tub of popcorn and a two-liter bottle of Coca-Cola. Let the Worst Pass is as entertaining as a Marvel movie and as over-the-top as the Godzilla saga. It's a romantic comedy starring Jennifer Aniston and Ben Stiller with the dramatic twists of Anna Karenina , the surprises of Borges's The Aleph, and the horrors of Lovecraft. It has dialogue by Cantinflas and the imagination of José Saramago, politicians with the flair of Moreno de Caro and the disturbing darkness of Kafka.

Nelson Camargo, the main character, is the protagonist and witness to a series of cosmic miracles, including the immortal Yeison, in a Bogotá perfectly mapped from the streets of Chapinero to the southern neighborhoods seen from the articulated TransMilenio buses. Camargo is a failed writer and a good-for-nothing professor who lives almost exclusively on cans of tuna. After being expelled from Insetec, a respected garage university, he has a life-changing encounter with a friend that will force him to listen to old metal bands in the bars of his youth, reread the pages of his only mediocre novel, and, above all, make his readers laugh out loud. This is a must-read.

Where would you place your novel, next to Anna Karenina, The Metamorphosis, or on a shelf of VHS movies?

I would put it next to Kurt Vonnegut's books; next to No News from Gurb by Eduardo Mendoza; and next to The Brotherhood of the Matchsticks by Stefano Benni.

The novel explores several literary classics and transforms them into brilliant, B-movie-inspired deliriums. What were your main literary and pop references when writing this crazy novel?

This is a novel with one foot in high culture and the other in popular culture. These are the ingredients of my education. I enjoy Cantinflas as much as Truffaut, I love video games and chess, I like comics and Magritte's paintings, and I've written prologues for books by Balzac and Zweig, but also for 008 Contra Sancocho by Hernán Hoyos . I have a weakness for artists, in all fields, who achieve this synthesis: Guillermo Cabrera Infante, Wes Anderson, Quentin Tarantino, and a long line of artists of whom I feel a disciple and follower.

García considers himself a disciple and follower of Quentin Tarantino. Photo: Julian Ungano

Nelson Camargo, the novel's protagonist, is your age and a caricature of an entire generation of writers. What was the process of creating this poor, failed, overweight, toothless, fifty-something writer?

I like antiheroes. The protagonist of Your House Is My House, my first detective novel, is a coward; the one in Human Resources is a poor worker, envious, unfaithful, and full of resentment; the one in Decline is weak-willed and boring. Nelson, the character in Let the Worst Happen, is part of that lineage. Paraphrasing Tolstoy, when he says that all happy families are alike, but unhappy ones are each unhappy in their own way, the loser and flawed character has more edges, more nuances than the successful one with emotional intelligence. I had many reservations about creating a writer character because they embody the author's pedantry in different ways. An antidote to that was to make this writer a failed, resentful, immature writer with significant gaps in his literary training. The challenge was to win the reader's indulgence despite all this.

The novel has a wild humor that, in reality, is quite rare in Colombian literature. Did you try out parts of the stories with your friends? What was their most complimentary comment?

One of my greatest blessings is having writer and reader friends who helped me refine the humorous aspects of the novel. More than praise, they pointed out moments where excess spoiled some passages. I am immensely grateful to them for that constructive criticism.

In a school, due to its adolescent strength, Whatever Happens would be an instant hit. Who do you think is your ideal reader?

I think this novel's readers are also outside of schools: in universities and prisons, at the supermarket checkout and in line at the bank, in the doctor's waiting room, in a restaurant with unpronounceable dishes, and in a dive bar that smells of weed and sweat. The potential reader of this novel is everywhere; it's designed so that even those without the literary references it has can still enjoy it.

Yeison is the novel's greatest stroke of genius. Who did he have in mind when creating him? Where did he come from?

The appearance of Yeison sets the novel in unexpected twists and turns. He's a character with literary origins, but one who required extensive research to make him believable and fit within the plot. I wanted Yeison to have a certain amount of light and shadow, to be menacing yet endearing, to be completely indecipherable at times. Much of the novel hinged on that.

Nelson's romance with a relative of Yeison's is one of the most punk moments in the story. How did the creation of the soundtrack for the novel come about?

Although there are references to Chiquetete and Sandro de América, Celia Cruz, and the Rolling Stones, my character is a metalhead and punk who knows the local scene. I think giving my character a particular musical taste made him more believable, and he also had to have his own opinions; that's why he likes La Pestilencia, but doesn't think the same about other metal and punk bands. These prejudices and dislikes extend, of course, to other groups and singers who aren't part of his tastes.

García toured the city where his characters lived to make it more believable. Photo: Margarita Mejía

What was your working method for writing this novel? How long did it take to write it?

I started Let the Worst Happen in April 2020, working six days a week without fail. After revising the first 100 pages of the novel, I had to rewrite and eliminate two secondary characters who were really hindering me and preventing me from moving forward. During the months of August and mid-September of that year, I locked myself away in a country house that Mario Duarte, lead singer of La Derecha and a supportive friend, had generously lent me, and wrote another 100 pages. I finished the last third of the novel at the end of 2022 and rewrote it during 2023. I revised the entire manuscript throughout 2024 and gave it a final pass at the beginning of this year.

The novel portrays the city very well, through its neighborhoods and its TransMilenio routes. What was the fieldwork like?

I tend to do a lot of research on the places where my stories take place. I arrive on the same means of transportation that appear, tour the locations, take photos, and make videos. In the case of the Policarpa neighborhood, where some scenes in the novel take place, I spent months accompanying a friend of mine whose job was to visit the neighborhood and talk to merchants to offer them wholesale fabrics. This way, he had someone to talk to and entertain himself with during the day, while I took notes, learned about the world, and developed the character of Reynaldo Mestizo, Yeison's father.

Did you ever feel sorry for Nelson? The poor guy suffers everything a human being can suffer.

I'm moved by their fate and grieve for it, but I try not to let compassion prevent the misfortunes that befall my characters. Being a character in my novels must be difficult because I'm very cruel.

Why did you make such a strong commitment? Did you feel spiritually that this novel was missing from Colombian literature?

I never questioned during writing whether I was going all in or not. Readers of the novel have pointed out that it's unlike anything else being written right now. I take that as a compliment and hope that, since that space was seemingly empty, the novel can settle there and find the readers who were looking for something similar. And I hope it can also captivate those who weren't looking.

Which film director would you like to see fall in love with the novel?

Since dreaming costs nothing, I think of Daniel Kwan and Daniel Sheinert, the directors of Everything, Everywhere at Once, and Spike Jonze, the director of Being John Malkovich.

Have you thought about a sequel? Let the Worst Happen II

I haven't thought of how I could continue that story from where I left off, but I do have an unpublished short story starring and narrated by Raquel, one of its characters. It's a story that predates everything that happens in the novel.

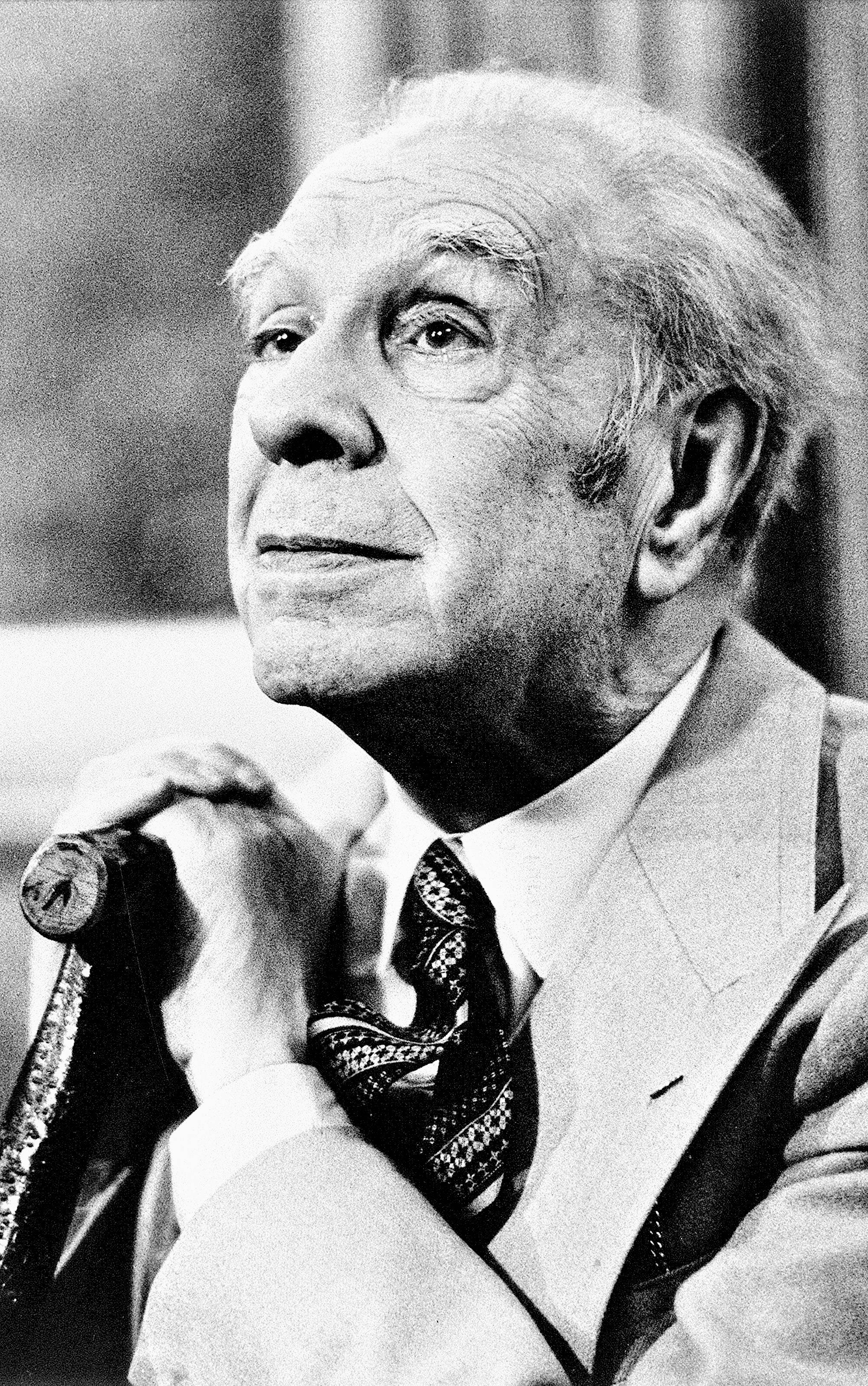

Jorge Luis Borges is the author of, among other marvels, The Aleph. Photo: EL TIEMPO Archive

And finally (those who read the novel will understand this question), what would Borges say about his story?

Borges was a very demanding reader. If he liked only "the first fifty years" of One Hundred Years of Solitude, what could he possibly think of Let the Worst Pass? I think his friend Bioy Casares might like the novel. I would feel more than rewarded for that.

Recommended: Andrea Echeverri's self-portrait

Andrea Echeverri, in her exhibition at the Cloister of San Agustín. Photo: César Melgarejo/EL TIEMPO

eltiempo

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2F7db%2F58e%2Fba5%2F7db58eba5465ac191d6a39adc428ee35.jpg&w=1280&q=100)

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2Fd7d%2Faaa%2F1b7%2Fd7daaa1b71429ead7363849d546a9ad2.jpg&w=1280&q=100)

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2F28a%2F1f4%2F608%2F28a1f4608318010b576f28554486a77b.jpg&w=1280&q=100)