Verónica Ortiz Lawrence finds in words a way to rebuild herself.

Verónica Ortiz Lawrence finds in words a way to rebuild herself.

The writer shares the aftermath of a foolish fall

in No Prayers for the Headless

▲ In her collection of poems, presenter and cultural promoter Verónica Ortiz Lawrence explores physical pain, spiritual anguish, and the need to understand why she survived tripping on a staircase and hitting her head against a wall. Photo: Luis Castillo

Daniel López Aguilar

La Jornada Newspaper, Monday, August 11, 2025, p. 2

Surrounded by two majestic bookshelves filled with short stories, novels and poetry, Verónica Ortiz Lawrenz (Mexico City, 1950) seems to be in another space.

She is no longer the restless, energetic woman who walked the streets, participated in television programs, and led open discussions about sexuality and politics. She now inhabits a more intimate world, where the green of the trees she observes from her window becomes a refuge and a symbol of life.

Almost four years ago, a foolish fall

transformed her life. Tripping on a staircase, she fell headfirst into a concrete wall. The injury was severe: her atlas, the first cervical vertebra just below the skull, was fractured into six fragments. The impact nearly cost her life and forced her to choose a different way of life.

Despite the after-effects, the writer, presenter, and cultural promoter returned to the literary scene with the poetry collection " No hay plegarias para los descabezados" (No hay prayers for the headless) (Fondo de Cultura Económica), in which she offers a harrowing account of that experience.

There are no survivors of the neck-breaking, there are no prayers for them. This book took three years to create. I'm alive to tell the tale, and that's almost a miracle

, she shared in an interview with La Jornada .

Two quotes, one from Lao-tzu and the other from D.H. Lawrence, introduce her work, composed of 30 texts born from this process. The author admitted that writing was, above all, a catharsis that traced the path of my personal grief, loss of faith, and constant search for meaning

.

In his verses, religion plays an important role. Despite having left the Catholic faith behind, the cry to God remains: God, these screws are not mine, they are yours. Why do you put them on me?

That question, which could have been a cry in the dark, becomes a persistent thought: it connects with physical pain, spiritual anguish, and the need to understand why he survived. "What am I doing here? What am I here for?"

he asks.

It wasn't just his body that suffered; he lost some of his hair, his left ear was working poorly, and his memory was playing tricks on him. "My mind was suddenly cloudy

," he added, "it's part of the blow to the head

."

Beyond the physical damage, the fracture brought with it a profound loneliness, reflected in long hours of introspection that allowed him to find in words a way to rebuild himself.

Reading and writing are healthy; I want to be close to Eros and far from Thanatos

, the author stated with conviction.

The woman who pioneered opportunities for sex education on Mexican television, at a time when talking about sex was taboo, now explores that same dimension from a corporeality marked by fragility.

This post is also a cry for forgiveness for the indifference she faced when visitors became scarce, kind words remained distant, and no one came forward to read aloud to her or simply to keep her company.

We have become so unreceptive to the pain and lives of others. This human disconnection, common these days, feels even more profound in my experience

, laments Verónica Ortiz, who had never thought of writing a volume of poetry.

The long reflections and paragraphs shared on Facebook with her followers gave way, thanks to the guidance of poet friends like Arturo Córdova Just, to verses that gave voice to the new Verónica, whom she had to learn to be

.

At 75, with a four-decade career in radio and television and eight published books, she is proud of her history, her voice, and her ability to reinvent herself. For her, poetry is the tool to name the unnameable, to recount the unprecedented, to share an intimate truth

.

Regarding what he hopes the reader will experience when approaching his work, he reflected:

"There's no need to fear the pain of others. I want anyone who reads this collection of poems to do so without prejudice, without fear of what they might find; on the contrary, I hope they connect with that pain, but also with the resilience I've found within it.

Poetry has the power to embrace the darkest aspects, and that's what I want to share: human fragility, suffering, but also the beauty that can be born from it all. Ultimately, it's a book that speaks of life, of the questions we ask ourselves, of the answers that never come, but also of hope, of the light that saves us.

"No Prayers for the Headless" will be presented on Thursday at 7:00 PM at the Rosario Castellanos bookstore of Fondo de Cultura Económica (Tamaulipas 202, Hipódromo Condesa neighborhood). The author will be accompanied by her colleagues Julia Santibáñez and Eduardo Casar.

Armando Fonseca, winner of the 16th Ibero-American Illustrated Catalog

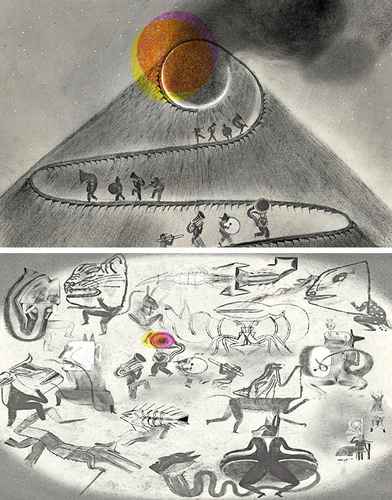

▲ Images from the series "In the Center of Silence, There's a Party ," by Armando Fonseca. Photo courtesy of the illustrator .

Anaís Ruiz López

La Jornada Newspaper, Monday, August 11, 2025, p. 3

Illustrator Armando Fonseca (Mexico City, 1989) was chosen as the winner of the 16th Ibero-American Illustrated Catalog, an award given by the SM Foundation in collaboration with the Guadalajara International Book Fair (FIL), with the series of four images In the center of silence, there is a party .

In an interview with La Jornada , he explained: "The story begins with some musicians who are invited to enter the crater of a volcano, where a party is taking place and a character wearing a death mask appears and dances with one of the musicians who carries a tuba, this giant instrument that wraps around the entire body. Then there is a transformation, which is what death does, but it is not only the end of life, but also the beginning, like the flower that is born from death, just as in Mesoamerican worldviews.

The series began to take shape when I heard a wind band in central Oaxaca. It created a kind of antenna in me, alert and receiving several signals at once to be able to represent it. Drawing is a gesture that leaves a mark, and when you read it, it speaks to you. I thought about community festivals in Mexico, which, despite their diversity, share common traits, such as the Day of the Dead festivals. I drew the characters, including animals and humans: there are felines, fish, rabbits, a crocodile, a scorpion, and a bull dancing together

, he said.

The philosopher also commented that in this work he wanted to capture coal, creating a very ashy landscape, an atmosphere similar to that of Juan Rulfo, where dust is the protagonist. I also sought to reflect my admiration for popular culture and art; I thought of the sones of Oaxaca and the son jarocho; also, in Latin America, such as cumbia and Cuban son. I was inspired by painters such as Francisco Toledo, Rufino Tamayo, Gilberto Aceves Navarro, José Luis Cuevas, the engraver José Guadalupe Posada, and the photographer Manuel Álvarez Bravo

.

Poetic atmosphere

Fonseca explained that the title of his series is due to a phrase mentioned by one of his favorite writers, Enrique Vila-Matas. I thought it could frame the scene, especially when they dance in the crater, because a volcano seems to be silent when it's asleep and only releases a few fumaroles, but in reality there is a magma that is dormant, ignited and very active. It seems like there is silence, but in reality there is music. This title also gave it a poetic atmosphere

.

The winner emphasized that a large part of his development as an illustrator "has been accompanying the award and seeing the selected winners over the 16 years the catalog has been open. In the first edition, the winner was Santiago Solís, followed by Gabriel Pacheco; both were my mentors. My friends Juan Palomino and Amanda Mijangos also won. I've entered the competition six times, as it's a benchmark in the world of illustration."

"It's good to see my previous work; I see it as very different from one another. You transform, and that's also interesting. When you compete, you develop your own work. It's about testing yourself and seeing what you're capable of or what's possible as an illustrator, and the result is often completely unexpected

," he stated happily.

Fonseca mentioned that, in the publishing world, illustrators often respond to the wishes and expectations of editors, the industry, or the author; in this competition, it's a bit of a chasm, because you have control over everything, so you don't know where to start or how to approach it. It's about creating a series of readable and articulate images; you have to think about how to make it understandable

.

Fonseca was chosen from among 682 works from 19 countries for the enormous quality of his graphic work and the original visual exploration of his illustrations, as well as the breadth of a symbolic universe rooted in the popular, with archetypal references reinterpreted in a poetic way

, as announced by the jury composed of Carolina Rey, Isabella del Monte, Andrea Fuentes Silva, Paulina Márquez and Pep Carrió, who, in addition to issuing the winner's decision, awarded special mentions to the artists María José de Telleria (Argentina), Saioa Aginako Lamarain (Spain), Paula Bustamante (Chile) and Rocío Katz (Argentina).

jornada