Leaders who put letters together

These are times of despotic air. Until a few years ago—at least in the West—the perception of the bloody dictator was a catastrophic peculiarity on the verge of extinction. Strangely, this is no longer the case. With a different style, different tactics, and different weapons, these shadowy figures persist. Just a few days ago, Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping, and Kim Jong-un enjoyed one of the most overwhelming displays of military power in living memory in Beijing. Beyond geopolitics and business, the three leaders all agree that they preside over their respective countries without any form of democratic control: Putin has been dictating the steps of the world's largest nation for more than a quarter of a century, the great Chinese leader has ruled a territory that is home to more than 17% of the planet's population without any opposition since 2013 (and the Chinese Communist Party, since 1949), and Kim Jong-un has ruled North Korea since 2011, although the Kim dynasty has been in power for more than 75 years.

There are other anniversaries. It was recently the centenary of the publication of Mein Kampf , and it will soon be half a century since the death of the dictator Franco. Hitler and Franco share a history of ignominy—each in their own style and with different results—but also a bizarre love of literature. And they were not alone in this. Many other dictators also published works.

The writer Daniel Kalder wanted to find out if there is such a thing as a dictatorial literary canon, and spent several years reading an amalgam of political theory, poetry, art criticism, journalistic pieces, and even romance novels written by dictators. He published The Infernal Library: On Dictators, The Books They Wrote, And Other Catastrophes Of Literacy (Henry Holt and Company, 2018).

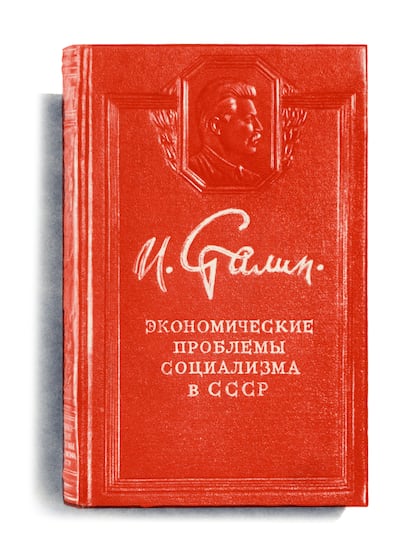

He read Mein Kampf from beginning to end. ―which had a Braille edition and a luxurious “bridal edition” for newlyweds―, Mussolini’s war diaries, Mao’s Little Red Book , and also the youthful verses of Stalin, a man who was so impressed by Alexander Kazbegi’s novel Parricide (1882) that he changed his name to Koba, after the main character, and used that pseudonym throughout his early career. He also obtained and studied Francisco Franco’s opinion pieces, Gaddafi’s Green Book , the romantic novel Zabiba and the King by Saddam Hussein, and even a treatise by Kim Jong-il, former supreme leader of North Korea and father of Kim Jong-un, entitled On the Art of Cinema .

After such an extreme exercise ―“An odyssey through the long, dark night of the dictatorial soul,” in his own words―, the news was not good: he was astonished by Hitler’s literalness about what he planned to do (for historian Konrad Heiden, Mein Kampf is painful proof of the world’s blindness and complacency, because its pages already announced a program of blood and terror “of such overwhelming frankness that few of its readers had the courage to believe it”).

In turn, Kalder credits Mussolini with providing a successful description of the brutality and desperation of the First World War. But, overall, what he found were brick-like harangues, sentimentality, boasting, and dull pages of endless tedium. About Mao's essay On Contradiction , published in 1937, Kalder writes that "it is as intricate as it is useless." "Reading it is like looking at a detailed model of a ship in a bottle: you wonder how its creator got there, while thinking that the energy would have been much better spent doing something else."

But where does this connection between books and dictators come from? It seems like a strange phenomenon, but perhaps it isn't so. After all, many of them were radical writers or journalists before becoming obscure leaders. "Mussolini was a highly successful editor and journalist, Lenin was a prolific writer of works on revolutionary politics, Stalin was a skilled editor, Mao dabbled in poetry..." Kalder reveals in an email conversation. They had a veneration for the written word and believed that by controlling texts they could "design human souls," according to Stalin's famous phrase.

The letter-blind attitude of the most powerful leaders rubbed off on many dictators in the developing world, who, according to Kalder, “suffered from status anxiety.” That's probably why Gaddafi wrote his Green Book as a response to Mao's Little Red Book , but others wrote as a means of personal expression. Hussein, for example—who authored works titled The Fortified Castle, Men and the City, and Demons of the Past— in his novel Zabiba and the King “clearly reflects the turmoil he experienced after the first Gulf War; his editor recounts that he continued writing even as American soldiers approached Baghdad and his end drew near,” Kalder notes.

Franco, magazine directorRegarding the dictator Franco, it's worth remembering his considerable foray into column writing and the fact that he held the number one membership in the Press Association. In his youth, he contributed to military newspapers such as El Telegrama del Rif and served as editor of the Revista de Tropas Coloniales , where he demonstrated his status as "a great admirer of the Portuguese integralism of Antonio Sardinha and the integral nationalism of Charles Maurras. That is, of a traditional, anti-liberal, corporatist, and medievalist state," explains Juan Carlos Sánchez, professor of journalism at the Carlos III University of Madrid.

Once the bloody Spanish Civil War was over, Franco returned to his literary and journalistic career. His best-known works are the novel Raza . Anecdotario para el guion de una película (Race. Anecdotes for the Script of a Film ), written under the pseudonym Jaime de Andrade, published in 1942—and immediately transformed into a feature film—and his contributions in the 1950s under various names (Jakim Boor, Hispanicus, Macaulay) to newspapers such as the Falangist Arriba (Arriba ), where he published more than 90 articles.

“In his writings,” according to Enrique de Aguinaga, “the influence of Admiral Luis Carrero Blanco, his closest collaborator for decades, was clearly evident. Among the military men of his generation, a literary itch was very common, especially in the form of autobiographical stories and occasional journalistic contributions. A kind of short-term outlet,” reveals Sánchez, author, along with Daniel Lumbreras, of the study Francisco Franco, columnist incognito (1945-1960) .

Whether outburst or not, writings always offer some clue about the author. These days, there are no strange mustaches à la Hitler or Mussolini, nor (almost) hysterical and threatening speeches, but the flagrant lack of personal, political, or social freedom—in very different degrees of ferocity—remains in more than 50 countries around the world. And, as could not be otherwise, in this 21st century, works by obscure leaders and leaders flourish: from Eritrea, Isaias Afwerki writes My Struggle for Eritrea and Africa ; from North Korea, Kim Jong-un leads Toward Final Victory ; Xi Jinping publishes books in China—and many other countries, in various languages—with titles as uncommercial as Ensuring a Decisive Victory in Building a Moderately Prosperous Society in All Respects and Strive for the Great Success of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era ; and Vladimir Putin, who in early 2000 published Judo . History, Theory and Practice , in 2023 he launched New World Order .

EL PAÍS

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2Fbbe%2Fdbf%2F69f%2Fbbedbf69fad383ea4422a82dc762fe8a.jpg&w=1280&q=100)

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2Fdff%2F996%2F533%2Fdff9965334471b6c668d090f1f16b67f.jpg&w=1280&q=100)