Johann Strauss in Vienna | Strauss Waltz: More than Um–ta–ta

On the Opernring , horse-drawn carriages stop in front of the magnificent Renaissance façade of the Vienna State Opera. Young men in historical clothing, including white powdered wigs, red tailcoats, and gold waistcoats, offer tickets for the evening's concert. Passersby stop and pull out their phones for a selfie. Amidst the hustle and bustle, a musician bows, raises his violin, and the bow glides over the strings. The first bars float through the air, battling with the urban noise. "On the Beautiful Blue Danube." This is what Vienna sounds like in the anniversary year of Johann Strauss , who was born almost 200 years ago, on October 25, 1825.

Ilse Heigerth is a renowned Strauss expert, author, and city guide. I'm traveling with her in Vienna—following the footsteps of the Waltz King, visiting the places where he once lived, performed, and married. "The State Opera, opened in 1869, is naturally the premier opera house in town—but for Strauss, it's also a symbol of a certain contradiction." Operetta was once frowned upon there. It's only allowed in once a year, on New Year's Eve. And then? "Die Fledermaus," of course. "A feel-good piece," says the expert, "funny, frivolous," and when it's sad, "funny-sad."

Johann Strauss was already a superstar in his time. Incidentally, his famous father, also a composer, bore the same name. Yet no other music symbolizes Vienna like that of Strauss Jr. Within the family dynasty, he wasn't the only composer: there was fierce competition between him and his father. Ultimately, his son, Johann, was more successful than his equally talented brothers—and than Strauss Sr. He wrote over 500 works: waltzes, polkas, marches, quadrilles, galops—and, of course, operettas.

The journey continues on the tram, as the Viennese affectionately call their streetcar. It squeaks around the bend to the next station: the Theater an der Wien. Heigerth points to the neoclassical building. "Almost all of Strauss's operettas premiered here," she says. "And he conducted them himself – often with a violin in his hand."

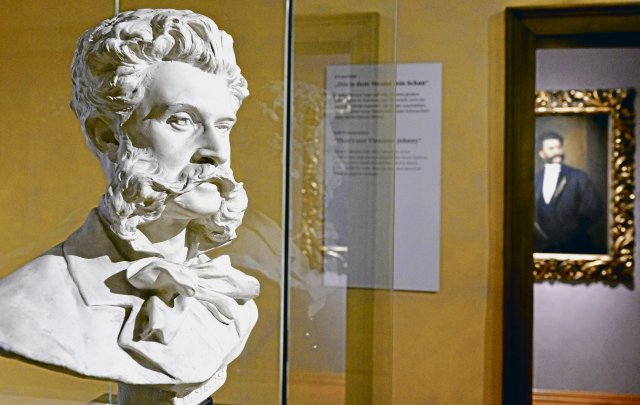

The beautiful SchaniWe're standing on the sidewalk, the faint sound of rehearsal singing drifts through a window. "He was a highly talented conductor," the tour guide tells us. He was known for his distinctive style: he wore small-checked trousers, a black tailcoat, a white waistcoat, and a necklace. When conducting, his movements were body-conscious. "He was a handsome man," Ilse Heigerth is certain of this. Back then, people called him "the handsome Schani." Today, he would probably be an influencer or TikTok star.

From the impressive theater, our path leads us to the "House of Strauss" – a multimedia interactive museum about the history of the Strauss family, located in the former Zögernitz Casino. Concerts are still held in the historic Strauss Hall. And here we're meeting a relative of the family: Eduard Strauss, unfolding a sheet of paper with a family tree. "Johann Strauss (son) is my great-great-uncle – just around the corner," he explains. With his mustache and striking features, you'd think you were standing face to face with Johann Strauss himself.

Eduard Strauss leads the tour through the colorful, multimedia museum. There isn't a single original object, but instead LED walls, sound installations, and animated projections provide expert information about the family's history—for example, about the suppressed reception of Strauss during the Nazi era. The Nazi regime stylized the Waltz King as a German cult figure—and to do so, suppressed his Jewish roots through document forgery. "Goebbels said: We can't do that, we can't ban Strauss—Hitler loved him so much. And then they simply Aryanized him," explains Eduard Strauss.

The grandmother of Johann Strauss Jr. was Jewish. The composer was summarily "whitewashed," his ancestry erased from the records. Eduard Strauss reveals the crude forgery of his baptismal register by the "Reichssippenamt" (Reich Family Office).

The museum is an audiovisual homage to the entire Strauss family. Johann, Josef, and Eduard – musical brothers, mocked by the arts pages of their time as "Jean, Peppi, and Edi." They were adored like members of a boy band – only with top hats instead of sneakers.

I ask him if his great-uncle was a wealthy man. "Oh yes," he's certain. "The operettas made him rich. There were royalties, and you could extract waltzes from every operetta and resell them. Multiple uses!" So, Johann Strauss was not only a brilliant composer, but also a shrewd businessman.

Love and ScandalStrauss was repeatedly drawn to Karlsplatz – a place that isn't a traditional square at all, but a spacious park with meadows, fountains, and art installations. Here, subway and tram lines, bike paths, and streams of tourists intersect – a mixture of everyday chaos and grand opera. A particularly romantic chapter for Strauss unfolded in the shadow of the baroque dome of St. Charles's Church, reports Ilse Heigerth. "Strauss married here. He was married three times. That wasn't easy in Catholic Austria."

Strauss's first wife, Henriette "Jetti" Treffz, an opera singer who was older than him, married him with great pomp. His third wedding, however, was a minor scandal. "Strauss had to change his citizenship and religion, becoming a Protestant and a citizen of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha—the Viennese still resent him for that," says Ilse, half serious, half mischievous.

What wouldn't you do for love? Strauss was engaged thirteen times. Adele Deutsch, his last wife, managed him until his death in 1899. Afterward, she took care of his estate. The musician had no children of his own with any of his wives. However, his curls were a coveted commodity among his female fans.

"There's more rupture than harmony in this music. 'Die Fledermaus' isn't just frivolous—it's also socially critical, anarchic. And that's what I want to show."

Roland Geyer Artistic Director of the Strauss Jubilee in Vienna

Heigerth tells a story that is typical of the composer's vanity: He dyed his hair and enjoyed giving out locks to female fans—until his wife Adele noticed and worried that he would soon go bald. So she took black poodles for walks and cut out a few tufts of hair. Hence, the Strauss curls.

Not far from Karlsplatz, Roland Geyer sits in his office. The cultural manager and theater director is the artistic director of the anniversary program "Johann Strauss 2025 Vienna , " which aims to break down the composer's image. "I don't want to create waltz kitsch," he says. "I want to show how modern and contradictory this man was."

The program includes over 65 productions at almost 70 venues – opera, dance, performance, and installations. Strauss is intended to be heard and seen in all 23 districts of Vienna. Geyer doubts how much people really know about Strauss. "Go out on the street and ask for a second work – many mistakenly say the Radetzky March. But that's by his father."

Strauss was pop, but also political. The Blue Danube Waltz was composed in 1866 and premiered in 1867 – shortly after the Battle of Königgrätz, which Austria lost to Prussia. The original text isn't about the Blue Danube, but about human suffering. "There's more rupture than harmony in this music," Geyer summarizes. "'Die Fledermaus' is not just frivolous – it's also socially critical, anarchic. And that's what I want to show."

"Rethinking Strauss"Rethinking Strauss – for Geyer, that also means doing away with big names and instead offering bold, cross-genre experiments, installations, and hands-on art. For example, with an escape room by Viennese artist Deborah Sengl. Her approach to the composer is very personal – she searches for ruptures and hidden facets beneath the brilliance. "In the Shadow of Doubt" is the title of her walk-through puzzle game – an associative approach to the celebrant's work.

Visitors must puzzle their way through lovingly designed rooms in the Museumsquartier. Amid puzzles, mirrors, and wall quotations, they discover a Strauss more torn than his image. "He was a genius, of course," says Sengl. "But also a man under the pressure of constantly delivering." The rooms are associative. You press buttons, open drawers, find letters, sketches, fragments of a biography. Nothing is clear—everything is ambiguous. Here, you encounter not the golden Strauss, but the doubtful, exhausted, imperfect artist and human being. "For me, that's the more exciting Strauss," emphasizes Sengl.

Strauss's legacy can also be found in Vienna's Stadtpark. A saxophone player blows "Viennese Blood" into the humid summer air. We follow the sound along winding paths, past mallards, joggers, and a busload of Asian tourists heading to a particular destination. A seemingly golden figure flashes between plane trees. The statue of Johann Strauss is Vienna's most photographed monument—and a selfie for the digital sofa show at home is a must. The composer stands framed by dancing river nymphs, which—depending on the perspective—embody the magic, but also the allure of the Danube.

A scene like something out of an operetta: a bit romantic, a bit frivolous, like the waltz: a dance that allowed men and women to be physically close, on an open stage – back in the 19th century. "Strauss was a revolutionary with rhythm," explains Heigerth. "The waltz was once considered offensive because men and women had to touch each other." The dance was originally a scandal. And at the same time, it had social explosiveness: a closeness that wasn't envisaged in the 19th century.

nd-aktuell